Lisinopril

Stefano M. Bertozzi MD, PhD

- Professor, Health Policy and Management

https://publichealth.berkeley.edu/people/stefano-bertozzi/

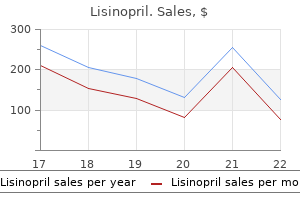

As mentioned briefly above heart attack or anxiety order lisinopril now, an additional issue regarding notification has to do with the age of the victims arteria mesenterica buy 2.5mg lisinopril with amex. While victims may be minors during initial prosecution 04 heart attack m4a order lisinopril 5mg, many continue to be victims in new cases into adulthood hypertension 1 order lisinopril on line. Therefore hypertension guidelines canada buy generic lisinopril line, guardians must evaluate when the victim should be told that images of their sexual abuse are in circulation or the frequency of the circulation in a manner intended to 76 minimize distress arrhythmia guidelines purchase lisinopril 5 mg without prescription. Guardians are faced with a quandary as to whether they should reveal the ongoing distribution early or wait until a child is closer to adulthood. This decision is more 77 difficult if the victim does not recall the initial abuse. As one parent described, I have been informed on a monthly basis of accounts where someone is being charged for having possession of her images that are on the internet. If my words can keep a pedophile off the streets to protect our young innocent children then that is what I need to do. Section 2259 of Title 18, United States Code, provides for mandatory and complete restitution for any victim harmed as a result of a 79 commission of a child pornography crime or other child sex crime. Section 2259 does not distinguish between production, distribution, receipt, or possession of child pornography with respect to victim status. If the offender committed one of those crimes and the victim was harmed by the commission of that crime, restitution is mandatory. Victims have sought and received restitution from child pornography production 80 offenders for some time. A small number of child pornography victims have started seeking to enforce this statutory right to restitution against child pornography possession, receipt, and 81 distribution offenders who may have no other connection to the victim. Courts have struggled with calculating restitution for this victim population and have reached different outcomes. While courts uniformly find that the child pornography victims are victims of the offenses and have suffered harm, many district courts refuse to order restitution because they find that the defendants crime is either not the proximate cause of the victims injury or that it is impossible 82 to apportion an amount of restitution to an individual defendant. By contrast, other district courts that have granted restitution have agreed that apportioning restitution is a challenge but have concluded that it is clear that child pornography victims are harmed as a result of the 83 84 commission of a crime and, thus, are entitled to an appropriate restitution award. Iowa 2010) (government failed to demonstrate the losses that the victim suffered as a result of defendants child pornography receipt offense); United States v. The United States Courts of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, Second Circuit, Ninth Circuit, D. Circuit, and Eleventh Circuit have held that child pornography victims are entitled only to losses that were proximately caused by the individual 85 offender who committed a non-production offense. By contrast, the en banc Fifth Circuit recently held that victims are entitled to restitution for a variety of losses without a showing of proximate cause, including for medical and mental services, transportation, lost income, and attorneys fees from those who offenders who possessed, received, or distributed child 86 pornography depicting the victims. Child pornography victims appear even less likely than other child sex abuse victims to report the abuse because of the existence of the images. Some of these victims live their lives wondering who has seen images of their sexual abuse and suffer by knowing that their images are being used for sexual gratification and potentially to lure new victims into sexual abuse. Because a victims image may be possessed in hundreds or thousands of cases, some victims report that the notification itself has exacerbated the harm. Nevertheless, without notification, victims may be unable to enforce other rights. The lower federal courts have grappled with legal issues related to restitution in non-production cases. The data in this chapter primarily are derived from two separate sources: (1) the Commissions regular annual datafiles of non2 production offenses for fiscal years 1992 through 2010; and (2) the Commissions special coding project of virtually all cases in which offenders were sentenced under the non-production guidelines in fiscal years 1999, 2000, and 2010, and cases from the first quarter of fiscal year 2012. Data in the special coding project supplement the annual datasets with more detailed information on offense conduct and offender characteristics. The first part of this chapter will discuss data from the Commissions annual datafiles, and the 3 remainder of the chapter will discuss data from the Commissions special coding project. In view of delays involved in the prosecution and sentencing of defendants under a new penal statute and guideline, the Commission relied on sentencing data beginning in fiscal year 1992. The difference in the two sets of cases relates to the fact that the Commissions special coding project excluded both cases with certain types of insufficient documentation and also cases sentenced under versions of the non-production guidelines applicable to offenses committed before November 1, 2004. With respect to data from the Commissions annual datafiles, the following analysis divides cases in which offenders were sentenced under the non-production guidelines into two primary offense types based on the manner in which the guidelines were applied: (1) receipt, transportation, and distribution offenses, as well as other similar but less common offenses. With respect to data from the special coding project, cases in which offenders were sentenced under the non-production guidelines are classified in greater detail based both on the 5 6 most serious offense of conviction and on real offense conduct in the case. During that period, there were several significant changes in the legal landscape concerning constitutional law, relevant statutes, and the guidelines that affected sentencing in child pornography cases. Although the Commissions annual datafiles contain information about the statutes of conviction, there are two reasons why classification of offense type is not based on offense of conviction for non-production cases contained in the Commissions annual datafiles. Thus, the guideline application in such cases is a better indicator of an offenders actual conduct than the statute of conviction. Second, receipt and distribution offenses appear disjunctively in the same statutory provision. The Commissions annual datafiles thus do not contain complete information about the specific offense of conviction (only the statute of conviction) in such cases. As discussed below, the Commissions special coding project examined indictments and judgments to determine the specific offense of conviction. By most serious offense the Commission refers to the following offenses of conviction in order of gravity (from most serious to least serious): distribution; importation; transportation (including shipping and mailing); receipt; morphing; and possession. The determination of degree of gravity of offense was based both on the statutory penalty ranges for the offense types (both minimums and maximums) and whether the sentencing guidelines provide for enhanced (or reduced) offense levels based on the offense conduct. For a discussion of statutory ranges of punishment and guideline application relevant to this determination, see Chapter 2 at 22-32. United States that departure decisions by federal sentencing courts were due significant deference and that 9 appellate courts should use an abuse of discretion standard in reviewing departures. Koon meant that district courts had greater discretion to depart from the sentencing guidelines than they did before the Supreme Courts decision. While measuring the actual impact of Koon on the departure rates is difficult, the downward departure rates increased from 1996 to 2003, including in child pornography cases, which led to a perception that Koon was, at least in part, 10 responsible. It also directly amended the child pornography sentencing guidelines to add a new enhancement relating to the number of images collected by an offender and made possession offenders eligible for other enhancements. Subsequent decisions by the Court further clarified both the sentencing courts discretion and appellate deference to below 7 Pub. Since Booker, sentencing courts have increasingly exercised their discretion 17 to impose below range sentences for non-production child pornography offenses. As discussed in Chapter 8, some appellate courts have approved a district courts categorical refusal to sentence in accordance with the child pornography guidelines based on a policy 18 disagreement. In addition to statutory and case law developments between 1987 and the present, the child pornography guidelines themselves have gone through several iterations based on both the Commissions own review and amendment process and also directives from Congress and other legislation regarding appropriate guideline penalties. In 21 the guidelines Sentencing Table, depending on the exact offense level at issue, an increase of 2 levels typically raises the corresponding guideline minimum. Not only have base offense levels increased during past two decades, new specific offense characteristics for non-production offenders have been added to increase guideline penalties. In 1992, R/T/D offenders were eligible to receive enhancements for three specific offense characteristics, while possession offenders were eligible to receive enhancements for two specific offense characteristics. Over the years, the non-production guidelines were amended at various points to add new enhancements. As a consequence, the corresponding guideline ranges for typical non-production offenders have increased 24 substantially. The information provided in this table concerns the current enhancements impacts or a particular enhancements impact as of its end date. Introduction the data analysis in this section relies primarily on the Commissions datafiles for non27 production child pornography cases from fiscal years 1992 through 2010. While offenders demographic characteristics have remained relatively stable, changes in the nature of offense conduct. The number of cases in which offenders have been sentenced under the non-production guidelines has grown substantially both in total numbers and as a percentage of the total federal case load. In fiscal year 1992, there were 16 possession cases, which increased to 904 cases in fiscal year 2010. Possession cases in which offenders did not have predicate convictions for sex offenses were 49. They constituted less than one-tenth of all non-production cases in fiscal year 2010. Non-production child pornography cases were prosecuted in every circuit and district, but the number of cases in each circuit and district varied substantially. With respect to the 94 districts, non-production cases occurred most frequently in the Eastern District of Missouri (72, 3. Such offenders did not face a mandatory minimum term of imprisonment and, in addition, the statutory classes of their offenses did not preclude probation 29 under 18 U. Possession offenders with predicate convictions and all offenders convicted of R/T/D offenses or production offenses are ineligible 31 for probation because they face mandatory minimum terms of imprisonment. Based on those maximum penalties, possession was a Class D felony, and R/T/D offenses were Class C felonies. In fiscal year 2010, nearly all offenders convicted of a non-production offense (1,688 of 34 1,715 or 98. Those 27 probationary sentences were spread throughout the country, in 17 different districts, and were imposed by 25 different district judges. Sentences of Imprisonment Since 1992, on a consistent basis, average sentences of imprisonment for offenders convicted of R/T/D offenses (R/T/D offenders) have been longer than average sentences for offenders convicted only of possession (possession offenders), which reflects the different 36 statutory and guideline provisions governing these offenses. Such an offender would not have been eligible for probation absent a downward departure. In 2010, the Sentencing Table was amended so as to increase Zone B one level upward. The proportion of offenders convicted of non-production offenses who received prison only sentences exceeded the overall average for all federal offenses in fiscal year 2010. For R/T/D offenders, the average prison sentence rose from 18 months in fiscal year 1992, to 71 months in fiscal year 2004, and to 129 months in fiscal year 2010. For possession offenders, the average prison sentence rose from 11 months in fiscal year 1992, to 34 months in fiscal year 2004, and to 63 months in fiscal year 2010. Both types of offenders average prison sentences were higher than the average prison sentence for all federal offenders in fiscal year 2010; the 39 overall average length of imprisonment for all federal offenders was 53. The within range rate for possession offenders decreased during post-Booker period to 39. Above range sentences have fluctuated but, like substantial assistance departures, have constituted a relatively small percentage of cases. Other Below Range includes downward departures and variances, less Substantial Assistance departures. Similarly, the government sponsored and non-government sponsored below range rates (excluding substantial assistance departures) for non-production offenses (55%) was higher than these combined below range rates for all federal offenses (33. This period is displayed separately because, beginning in fiscal year 2005, the Commission changed its methodology in collecting information on sentence length relative to the applicable guideline range in response to 40 Booker. Both government sponsored and nongovernment sponsored below range sentences increased after Booker for offenders sentenced under the non-production guidelines. As a result, fiscal year 2005 is reported as the partial year from January 12, 2005, through September 30, 2005. The rate of non-government sponsored below range sentences in such cases increased to 45. The rate of non-government sponsored below range sentences in such cases increased to 51. As the figures demonstrate, in possession cases, the average sentence remained quite close to the average guideline minimum before Booker.

Many transsexual and transgender persons who acknowledge a history of autogynephilic arousal report that their autogynephilic feelings have continued throughout their lives; others arrhythmia technologies institute order lisinopril 2.5 mg free shipping, however blood pressure 10 order discount lisinopril on line, state that their autogynephilic feelings have waned or disappeared blood pressure phobia cheap lisinopril 2.5 mg free shipping. Most participants in both groups appeared to have been in their 40s or 50s when surveyed hypertension 2014 guidelines buy lisinopril 5 mg free shipping. In interpreting these gures blood pressure medications with the least side effects order lisinopril with american express, it is important to remember that autogynephilic arousal is probably greatly underreported arrhythmia 24 buy lisinopril discount, for the reasons explained in Chap. I have suffered with autogynephilia since I rst became aware of my feelings at age 4. From about age 12 or 13, the idea of being able to wear womens clothes and present and live as a woman was an amazing sexual turn-on, and it remains so to this day. I am still aroused by the thought of having a female body, but the requirement to masturbate has all but disappeared. Imagining myself a woman has always been sensually pleasurable, whether accompanied by climax or not. I would like to say the arousal and pleasure are now gone or irrelevant, but I would be lying. I admit that I have many sexual fantasies about being female and having a female body, a lifelong dream for me. After starting hormone therapy and living in female role for a while, the fantasies continued like they always had, only now there was more satisfaction from having them. Even now, I embrace my autogynephilic fantasies as part of my sexuality, which is alive and very well. But sometimes Ill look in the mirror as I head out to work and feel a ush of excitement over who I have become. Preoperatively, I had some sexual arousal when wearing womens clothes; postoperatively, I have felt arousal in the vulva when wearing lingerie. Preoperatively, when I was fantasizing myself to be a woman with a vagina, I was strongly sexually aroused and got an orgasm. But I have had moments where I have had a total orgasmic rush because of the transformation in myself and my body. In self-pleasuring, I do think about what I have done at times and that does sexually excite me, I must admit. In my teens, I behaved like a typical transvestite, cross-dressing and masturbating in private. I also had the usual forced feminization fantasies, so typical of transvestites, and now I realize, transsexuals, too. Sexually, I still get aroused by forced feminization fantasies and being the woman among men. Even though I only rarely masturbate now, I typically do so while looking at myself in the mirror. Standing naked in front of a mirror was all that was necessary to renew the warmth that I felt. I have been sexually aroused since surgery and would readily admit that the sensation is indistinguishable from the above mentioned warmth. Second, this observation calls into question an alternative explanation of autogynephilia that has been proposed by some critics of Blanchards 92 5 Developmental Histories theory. This explanation asserts that autogynephilia is merely an epiphenomenon that emerges when males who have female gender identities and incongruent male bodies fantasize about having female bodies in order to have satisfying sexual experiences. Serano (2010) summarized this explanation: It makes sense that pretransition transsexuals (whose gender identity is discordant with their physical sex) might imagine themselves inhabiting the right body in their sexual fantasies and during their sexual experiences with other people. Indeed, critics of autogynephilia theory have argued that such sex embodiment fantasies appear to be an obvious coping mechanism for pretransition transsexuals. I am 47 years old, post-operative by 1 month, and clearly identify with the feelings you describe. I was aware that something like autogynephilia could be driving me and I made sure that I could function in a female body before committing to my surgery. I revisited old thoughts and fantasies and ultimately found that some of those res still burned. To make it happen, I had to turn up the heat, so to speak, and add intensity and violence to them. I still like to play with some of the old fantasies, but they are much more gentle and loving now. In many cases, resurrecting their earlier autogynephilic fantasies facilitates high levels of erotic arousal and eventually enables clients to achieve orgasm. The excerpts also demonstrate that signicant numbers of autogynephilic transsexuals report that they were not effeminate in childhood or adulthood but were instead unremarkably masculine in their interests and behaviors, even though they intensely desired to make their bodies resemble womens bodies and live and be recognized as women. Are (or were) nearly all autogynephilic transsexuals unremarkably masculine men whose gender dysphoria was simply an outgrowth of their paraphilic desire to turn their bodies into facsimiles of womens bodies I believe that the narratives presented in this chapter support that interpretation, but they obviously cannot settle the issue. The value of these narratives does not lie in their ability to prove or disprove any theoretical proposition, but in their capacity to inform the decisions that severely gender dysphoric autogynephilic men face. This information is likely to be of signicant value to severely gender dysphoric autogynephilic men who are considering sex reassignment but feel deterred by the realization that they lack intrinsic femininity. Chapter 6 Manifestations of Autogynephilia Four Main Types of Autogynephilia Blanchard (1991) described four distinct types or categories of autogynephilic fantasies and behaviors: transvestic (involving wearing womens apparel), anatomic (involving possessing female anatomic features), physiologic (involving having female physiologic functions), and behavioral (involving engaging in stereotypically feminine behavior). The most prevalent type of partial autogynephilia involves the desire to have womens breasts but no desire to have female genitals. It is debatable whether individuals who experience this type of partial autogynephilia should be considered transsexual; for purposes of this study, I have chosen to categorize them as nontranssexual. Chapter 1 1 includes several narrative excerpts by informants who experienced partial autogynephilia. The four types of autogynephilia that Blanchard described are conceptually useful but are not mutually exclusive. Some autogynephilic fantasies and behaviors could easily be classied under more than one category; for example, wearing a menstrual pad could be considered a manifestation of transvestic, behavioral, or physiologic autogynephilia, depending on its meaning to the person wearing it. The various types of autogynephilia also tend to co-occur; in particular, most individuals who experience anatomic autogynephilia also experience transvestic and behavioral autogynephilia. There are some notable exceptions to this pattern, however: A few informants who reported anatomic autogynephilia denied any desire to engage in female-typical behaviors or to live in a female-typical gender role. One particular type of behavioral autogynephilia, the act or fantasy of engaging in sexual activity with a man as a woman (a manifestation of autogynephilic interpersonal fantasy; Blanchard, 1989b) is both highly prevalent and of particular theoretical and clinical signicance; it will be considered separately in Chap. Most informants acknowledged or alluded to transvestic autogynephilia in their narratives. The narrative excerpts in this section illustrate important general principles about transvestic autogynephilia, are noteworthy or unusual, or emphasize fetishistic elements not generally associated with MtF transsexualism. Here are three representative accounts: I am a transgender woman currently undergoing estrogen treatment. My earlier closet phase involved the ritual of dressing as a normal woman: lingerie, nylons, dresses, shoes, etc. By my mid-20s, I had very strong desires to dress as a female on a full-time basis and to attract attention as a sexy, feminine woman. I have worn sexy feminine fashions, especially bras, lingerie, pantyhose, short dresses, lace fashions, mini-skirts, high heels, etc. Wearing sexy lingerie, a bra, a girdle with nylon stockings or sensuous sheer pantyhose, and high heels, imagining myself as a female, still often sexually arouses me, leading to an erection, masturbation, and orgasm. My counselor classies me as a transsexual and has offered to refer me for hormone therapy. In college and law school, under the guise of being a hippie, I wore long hair, womens jeans, and womens T-shirts. I married, and my cross-dressing became the secretive wearing of my wifes clothes, always in front of a mirror. But cross-dressing adds so much more: In front of a mirror, it gives the visual image of a woman in my presence, the touch of silk fabrics and feminine underclothes, the touch of smooth skin, the smell of cosmetics, etc. It just feels so good to be dressed and acting as a woman that nothing else compares. This illustrates why it is useful to think of transvestism as transvestic autogynephilia: cross-dressing that facilitates the thought or image of oneself as a female. Blanchard (1991) explained: the rationale for subsuming transvestism under the heading of autogynephilia is that the transvestites excitement results from making himself, in some sense, more like a woman. In fact, most transvestites do fantasize themselves as females when they are crossdressing and may also act this out in their behavior. No, it is the form follows function aspect of womens clothes that excites me most. Thus having to wear a bra for supporting my breasts, or having to wear panties that have a closed crotch, in recognition of the fact that my penis has been removed and that I now have the external genitalia of a female. Levine (1993) commented that I cannot ever recall speaking to or hearing about an adult cross-dresser who did not have a fantasy of himself as a female. I now assume that the cross-dressing and the autogynephilic fantasy are the external and internal manifestations of the same phenomenon. One informant who was especially aroused by wearing womens panties early in her cross-dressing career reported that the scope of her erotic cross-dressing subsequently broadened to include other items of womens attire: I have always found crossdressing extremely erotic and very sexually satisfying. I was more interested in what style of panties they were wearing or what I was going to wear when I got home from school. In my twenties, I began to acquire bras, nightgowns, nylons, and other types of lingerie. Two individuals favored high-heeled shoes: Your article on autogynephilia very accurately characterized the core experience of my life. My earliest fantasies simply involved being a cute little female with large breasts. This evolved over time into enormously detailed fantasies, 98 6 Manifestations of Autogynephilia which included taking showers as a woman (but wearing high heels) and different sorts of sexual intercourse. In my fantasies, I imagine the sensation of a mans hands on my hips, pulling me down to make penetration deeper. For quite some time, sex with women has required me to pretend that Im the female being penetrated to achieve orgasm. I am 6 feet tall, like all the runway models, with a size 9-1/2 womens pump, and open toe strappy sandals are my favorite. Even though my age should call for a cooled-down version of attire, I much prefer the hotter, younger styles. I have been playing ice hockey for years, and my behind and long legs are really something to see. Autogynephilic transsexuals are theorized to want to become facsimiles of the kinds of women to whom they are sexually attracted, so it is not surprising that most would prefer to resemble young, sexually desirable women and would be drawn to the attire that young women who wish to project a sexy image stereotypically favor. One informant had a special fondness for another particular type of womens footwear, Keds tennis shoes: I remember nding my mothers stockings and garters sometime around age 8 or 9, and that is when I started trying womens clothes on. My wife understands that I wish that I was female and lets me buy and wear womens clothing; for the most part I do it when I am alone. I wear things like womens sandals, Keds tennis shoes (I have found Keds very sexy since I was in third grade), panties, tops, pants, shorts, and bathing suits. Their reports could be interpreted as describing transvestic autogynephilia that occurred in the service of behavioral autogynephilia. The following narratives are illustrative: I began cross-dressing shortly after puberty in my older sisters clothes. Later, I would occasionally borrow one of my wifes dresses when she was out of town. I have come to realize that for me, being a cross-dresser has not merely been the activity of a transvestite, but of a transsexual. The clothes themselves are but an adornment that allow me to take on the intended role. A skirt or dress, because of its very construction, makes a woman vulnerable, which is a female attribute. Trying to avoid a neighbors excitable little terrier causing a run in my pantyhose when he runs to greet me. Transvestic Autogynephilia 99 Transvestism as a Relaxing or Comfortable Activity Heterosexual transvestites, who resemble autogynephilic transsexuals in many respects, often report that cross-dressing makes them feel relaxed or comfortable. In a survey of 33 heterosexual cross-dressers, Buhrich (1978) found that the most prevalent feelings his subjects described during cross-dressing were comfortable, relaxed, at ease (p. Buhrichs subjects reported that during adolescence, these feelings had been slightly more prevalent than sexual arousal; in later adulthood they were much more prevalent than sexual arousal. In the current study, several transsexual informants similarly reported that cross-dressing was not only sexually arousing but also made them feel comfortable or relaxed. Here are some representative narrative excerpts: When I reached adolescence, I started cross-dressing discretely and would get aroused and masturbate. After the sexual part of the experience, I would remain dressed as long as was safe and would feel comfortable and cozy. It was interesting that, although I was excited to get dressed in female clothing, once dressed, I was always very relaxed and any emotional excitement subsided. I still dress, but it is more a stress reliever now than a form of sexual arousal.

Order lisinopril 2.5mg on-line. How to measure blood pressure using a manual monitor.

A common example of this is the stroboscopic effect blood pressure 9870 order lisinopril 10mg mastercard, used in movies or flip books blood pressure medication make you cough discount 5mg lisinopril with visa. Images in a series of still pictures presented at a certain speed will appear to be moving hypertension for dummies buy lisinopril 5mg with visa. Another example you have probably encountered on movie marquees and with holiday lights pulse pressure uk generic lisinopril 5 mg, is the phi phenomenon blood pressure upon waking purchase lisinopril amex. A series of lightbulbs turned on and off at a particular rate will appear to be one moving light blood pressure medication zapril purchase lisinopril 5 mg without prescription. If a spot of light is projected steadily onto the same place on a wall of an otherwise dark room and people are asked to stare at it, they will report seeing it move. Depth Cues One of the most important and frequently investigated parts of visual perception is depth. Without depth perception, we would perceive the world as a two-dimensional flat surface, unable to differentiate between what is near and what is far. Researcher Eleanor Gibson used the visual cliff experiment to determine when human infants can perceive depth. An infant is placed onto one side of a glass-topped table that creates the impression of a cliff. Actually, the glass extends across the entire table, so the infant cannot possibly fall. Gibson found that an infant old enough to crawl will not crawl across the visual cliff, implying the child has depth perception. Other experiments demonstrate that depth perception develops when we are about three months old. Researchers divide the cues that we use to perceive depth into two categories: monocular cues (depth cues that do not depend on having two eyes) and binocular cues (cues that depend on having two eyes). If you wanted to draw a railroad track that runs away from the viewer off into the distance, most likely you would start by drawing two lines that converge somewhere toward the top of your paper. You would draw the boxcars closer to the viewer as larger than the engine off in the distance. A water tower blocking our view of part of the train would be seen as closer to us due to the interposition cue; objects that block the view to other objects must be closer to us. If the train were running through a desert landscape, you might draw the rocks closest to the viewer in detail, while the landscape off in the distance would not be as detailed. This cue is called texture gradient; we know that we can see details in texture close to us but not far away. By shading part of your picture, you can imply where the light source is and thus imply depth and position of objects. We see the world with two eyes set a certain distance apart, and this feature of our anatomy gives us the ability to perceive depth. It knows that if the object is far away, the images will be similar, but the closer the object is, the more disparity there will be between the images coming from each eye. As an object gets closer to our face, our eyes must move toward each other to keep focused on the object. The brain receives feedback from the muscles controlling eye movement and knows that the more the eyes converge, the closer the object must be. Effects of Culture on Perception One area of psychology cross-cultural researchers are investigating is the effect of culture on perception. Research indicates that some of the perceptual rules psychologists once thought were innate are actually learned. For example, cultures that do not use monocular depth cues (such as linear perspective) in their art do not see depth in pictures using these cues. Also, some optical illusions are not perceived the same way by people from different cultures. People who come from noncarpentered cultures that do not use right angles and corners often in their building and architecture are not usually fooled by the Muller-Lyer illusion. Cross-cultural research demonstrates that some basic perceptual sets are learned from our culture. Our sense of smell may be a powerful trigger for memories because (A) we are conditioned from birth to make strong connections between smells and events. In a perception research lab, you are asked to describe the shape of the top of a box as the box is slowly rotated. The blind spot in our eye results from (A) the lack of receptors at the spot where the optic nerve connects to the retina. Smell and taste are called because (A) energy senses; they send impulses to the brain in the form of electric energy. What is the principal difference between amplitude and frequency in the context of sound waves Gate-control theory refers to (A) which sensory impulses are transmitted first from each sense. Which of the following sentences best describes the relationship between sensation and perception Color blindness and color afterimages are best explained by what theory of color vision You are shown a picture of your grandfathers face, but the eyes and mouth are blocked out. Which of the following sentences best describes the relationship between culture and perception This connection may explain why smell may be a powerful trigger for emotions and memories. This connection has nothing to do with learning, long-term memory, or deep processing. Smells are eventually communicated to the cortex, but that does not explain the special connection to memory. The hammer, anvil, and stirrup transfer vibrations to the cochlea, not the other way around. The semicircular canals send messages to the brain about the orientation of the head and body. This experiment would not be investigating feature detectors, because the equipment required to measure the firing of feature detectors is not described. Placement of rods and cones in the retina would not affect perception of the top of the box. Binocular depth cues are probably not the target of the research because the researchers are not asking questions about depth. However, these do not occur in everyone, and the question implies the blind spot present in everyones eyes. Choice D is incorrect because all nerve impulses are sent by an electrochemical process. Frequency is the measure of how quickly the waves pass a point, causing the pitch of the sound. This theory is specific to the sense of touch, so choices A, C, and D are incorrect. Choice E is incorrect because gate-control theory has to do with the perception of pain, not how we interpret sensations in general. When an object is close to our face and our eyes have to point toward each other slightly, our brain senses this convergence and uses it to help gauge distance. Some researchers think part of perception may happen in the senses themselves, so choice C is incorrect. The rest of the items are incorrect because they describe functions the retina does not perform. The example does not reflect bottom-up processing because information is being filled in, instead of an image being built from the elements present. Signal detection theory has to do with what sensations we pay attention to , not filling in missing elements in a picture. Gestalt theory might relate to this example because you are trying to perceive the picture as a whole, but there is no such term as gestalt replacement theory. However, some perceptual sets are learned and will vary, so choices A and B are incorrect. Sensory apparatuses do not vary among cultures, and perception is not genetically based as implied in choice E. Early psychologists such as William James, author of the first psychology textbook, were very interested in consciousness. However, since no tools existed to examine it scientifically, the study of consciousness faded for a time. Currently, consciousness is becoming a more common research area due to more sophisticated brain imaging tools and an increased emphasis on cognitive psychology. The historical discussion about consciousness centers on the competing philosophical theories of dualism and monism. Dualists believe humans (and the universe in general) consist of two materials: thought and matter. Thought is a nonmaterial aspect that arises from, but is in some way independent of, a brain. Some philosophers maintain that thought is eternal and continues existing after the brain and body die. Monists disagree and believe everything is the same substance, and thought and matter are aspects of the same substance. However, psychologists are trying to examine what we can know about consciousness and to describe some of the processes or elements of consciousness. Psychologists define consciousness as our level of awareness about ourselves and our environment. We are conscious to the degree we are aware of what is going on inside and outside ourselves. While you are reading this text, you might be tapping your pen or moving your leg in time to the music you are listening to . One level of consciousness is controlling your pen or leg, while another level is focused on reading these words. Research demonstrates other more subtle and complex effects of different levels of consciousness. The mere-exposure effect (also see Chapter 14) occurs when we prefer stimuli we have seen before over novel stimuli, even if we do not consciously remember seeing the old stimuli. For example, say a researcher shows a group of research participants a list of nonsense terms for a short period of time. Later, the same group is shown another list of terms and asked which terms they prefer or like best. The mere-exposure effect predicts that the group will choose the terms they saw previously, even though the group could not recall the first list of nonsense terms if asked. Research participants respond more quickly and/or accurately to questions they have seen before, even if they do not remember seeing them. Another fascinating phenomenon that demonstrates levels of consciousness is blind sight. Some people who report being blind can nonetheless accurately describe the path of a moving object or accurately grasp objects they say they cannot see! One level of their consciousness is not getting any visual information, while another level is able to see as demonstrated by their behavior. The concept of consciousness consisting of different levels or layers is well established. Not all researchers agree about what the specific levels are, but some of the possible types offered by researchers are shown in the following. Conscious the information about yourself and your environment you are currently aware of. Your level conscious level right now is probably focusing on these words and their meanings. Nonconscious Body processes controlled by your mind that we are not usually (or ever) aware of. Right level now, your nonconscious is controlling your heartbeat, respiration, digestion, and so on. Preconscious Information about yourself or your environment that you are not currently thinking about level (not in your conscious level) but you could be. If I asked you to remember your favorite toy as a child, you could bring that preconscious memory into your conscious level. Subconscious Information that we are not consciously aware of but we know must exist due to behavior. Unconscious Psychoanalytic psychologists believe some events and feelings are unacceptable to our level conscious mind and are repressed into the unconscious mind. See the section on psychoanalytic theory in Chapter 10 for more information about the unconscious. Many studies show that a large percentage of high school and college students are sleep deprived, meaning they do not get as much sleep as their body wants. During a 24-hour day, our metabolic and thought processes follow a certain pattern. Some of us are more active in the morning than others, some of us get hungry or go to the bathroom at certain times of day, and so on. We might experience mild hallucinations (such as falling or rising) before actually falling asleep and entering stage 1.

He was hospitalized after threatening a woman hypertension prevention cheap 10 mg lisinopril overnight delivery, [again] after attacking two strangers at a Burger King [and yet again] after ghting with an apartment mate hypertension of the lungs buy lisinopril pills in toronto. Dangerousness arrhythmia grand rounds buy discount lisinopril 5 mg on line, a legal Dangerousness term hypertension pathophysiology lisinopril 5 mg generic, refers to someones potential to harm self or others blood pressure medication iv order lisinopril 2.5 mg otc. Determining whether the legal term that refers to someones someone is dangerous pulse pressure 25 order lisinopril with amex, in this sense, rests on assessing threats of violence to self potential to harm self or others. Dangerousness can be broken down into four components regarding the potential harm (Brooks, 1974; Perlin, 2000c): 1. Prior to each discharge from a hospital or psychiatric unit, Goldstein had to be evaluated for dangerousness; he was then discharged because he was deemed not dangerous, or not dangerous enough. Researchers set out to determine the risk factors that could best identify which patients discharged from psychiatric facilities would subsequently act violently. For more information see treatment in a psychiatric hospital and is about to be released but is perceived the Permissions section. Ethical and Legal Issues 731 To prevent such people from harming themselves or others, the law provides that they can be conned as long as they (continue to) pose a signicant danger. When clinicians evaluate present and future dangerousness, they base their judgment (in part) on an individuals history of such behavior, but such information provides only limited guidance (Perlin, 2000c; Schopp & Quattrocchi, 1984). In fact, whether someone is an imminent danger to self or others is often not clear. For example, although the possible dangerous acts the person may commit should be imminent, exactly how this word is dened remains unclear (Meyer & Weaver, 2006). Actual Dangerousness Mentally ill individuals who engage in criminal acts receive a lot of media attention, which may lead people to believe that criminal behavior by those with mental illnesses is more common than it really is (Pescosolido et al. In fact, criminal behavior among the mentally ill population is no more common than it is in the general population (Fazel & Grann, 2006). However, two sets of circumstances related to mental illness do increase dangerousness: (1) when the mental Although some people with mental illness may illness involves psychosis, and the person may be a danger to self as well as others create a public nuisance, like this man yelling at voices that only he can hear, such public dis(Fazel & Grann, 2006; Steadman et al. It is worth stressing a cautionary note: Although in this section we have focused on the relation between some forms of mental illness and violence, as occurred with Goldstein, most mentally ill people are not violent. Indeed, if they are in jail or prison, it is usually for minor nonviolent offenses related to either trying to survive. The police briey restrained him, but they determined that he was rational and not a threat to Tarasoff. Tarasoff was out of the country at the time, but neither she nor her parents were alerted to the potential danger. Her parents sued the psychologist, saying that Tarasoff should have been protected either by warning her or by having Poddar committed to a psychiatric facility. In what has become known as the Tarasoff rule, the Supreme Court of California (and later courts in other states) ruled that psychologists have a duty to protect potential victims who are in imminent danger (Tarasoff v. The Tarasoff rule effectively extended a clinicians duty to warn of imminent harm to a duty to protect. Note, however, that potential danger to property is not sufficient to compel clinicians to violate condentiality (Meyer & Weaver, 2006). Maintaining Safety: Conning the Dangerously Mentally Ill Patient A dangerously mentally ill person can be conned via criminal commitment or civil commitment, described in the following sections. Criminal Commitment Criminal commitment is the involuntary commitment to a mental health facility of a person charged with a crime. Indiana, 1972), it is illegal to conne someCriminal commitment the involuntary commitment to a mental one indenitely under a criminal commitment. Thus, a defendant found not comhealth facility of a person charged with a petent to stand trial cannot remain in a mental health facility for life. Judges have discretion about how Ethical and Legal Issues 733 long they can commit a defendant to a mental health facility to determine whether treatment may lead to competence to stand trial. In this case, the process of deciding whether he or she should be released from the mental health facility proceeds just as it does for anyone who hasnt been criminally charged. If the individual is deemed to be dangerous, however, he or she may be civilly committed. Civil Commitment When an individual hasnt committed a crime but is deemed to be at signicant risk of harming himself or herself, or of harming a specic other person, the judicial system can conne that individual in a mental health facility, which is referred to as a civil commitment. There are two types of civil commitment: (1) inpatient commitment to a 24-hour inpatient facility, and (2) outpatient commitment to some type of monitoring and/ or treatment program (Meyer & Weaver, 2006). Civil commitment grows out of the idea that the government can act as a caregiver, functioning as a parent to people who are not able to care for themselves; this legal concept is called parens patriae. The interplay between dangerousness, duty to warn, and civil commitment is illustrated by what happened to Mr. He is inclined to interpret the words and actions of others idiosyncratically, and he characteristically avoids situations that require interpersonal exchanges. He manages to provide for his basic tangible needs, but he remains emotionally withdrawn and interpersonally isolated. He lives in a rooming house populated primarily by residents who have had mental health difficulties. He has no friends among the residents, but he ordinarily gets along in the house without serious difficulty by limiting interaction with the other residents. In each of the rst two incidents, he struck another individual, causing minor injuries involving bruises and abrasions. Following the second conviction, he served 60 days in the county jail and was released on parole. In the third incident, he struck a coworker with a wrench, causing serious but not permanent or life-threatening injuries. During legal proceedings following each assault, various participants in the legal system realized that he suffered some psychological disorder, but none believed that his impairment was sufficient to support an insanity defense or civil commitment. He refused to seek treatment after the rst conviction, but he began attending weekly psychotherapy sessions as a condition of his release on parole following the second conviction, and he returned to therapy following release from jail following the third offense. The treating psychologist has diagnosed Smith as suffering from a personality disorder with schizoid and paranoid features. Although he is no longer on parole, Smith has continued attending the weekly sessions. During these sessions, he expressed his belief that the convictions were unfair because in each case he had struck out to protect himself from others who had begun watching him, picking on him, and looking for an opportunity to harm him. During the last few sessions, Smith told the psychologist that now, theyre starting again. As they were leaving work early in the morning, Brown stated, be careful and watch your step out there. The involuntary commitment to a mental the psychologist encouraged Smith to consider alternative interpretations of Browns comhealth facility of a person deemed to be at ments. When Smith seemed unable to consider any alternative interpretation, the psycholosignicant risk of harming himself or herself gist became increasingly concerned that Smiths reality testing was deteriorating and that or a specic other person. The psychologist considered the possibility that a joint session with Smith and Brown might help reduce the risk of another assault. Specically, Smith might consider alternate interpretations and become reassured that these remarks were innocent, or Brown might realize that it would be advisable to discontinue making such remarks to Smith. Smith responded to the psychologists suggestion for a joint meeting by becoming increasingly agitated, and he yelled that he had thought their conversations were secret and that he would never again see the psychologist if their conversations were shared with anyone. The psychologist considered the following [types of] interventions, some of which are mutually compatible: (a) increase the frequency of therapy sessions; (b) emphasize a cognitive reframing of Smiths interpretations of Browns comments; (c) encourage Smith to explore alternative means of protecting himself from the perceived danger, such as always leaving work at the same time other people leave or always walking home from work on well-lit streets; (d) refer Smith to the clinic psychiatrist for medication review; (e) encourage Smith to consider voluntary inpatient care, particularly if the apparent deterioration worsens. The psychologist realized that if such approaches failed to ameliorate Smiths deterioration, or if she believed that the risk of another assault was severe or imminent, delegated preventive action [such as civil commitment] might be warranted. Because Smiths functioning seemed unlikely to meet the jurisdictions criteria for civil commitment, a warning of some kind would be the available delegated intervention. She would be hesitant to warn, however, because she knew of no empirical evidence that warnings reduce violence, and she believed that Smith would view such action as a betrayal and discontinue therapy. Further isolation might also occur if the warning resulted in his dismissal from his job or in counterproductive responses from Brown. The psychologists prior clinical interventions, primarily cognitive reframing and support, had been effective in ameliorating her clients inclination toward persecutory interpretations of events and in managing the risk associated with exacerbation of these tendencies. She realized that she had no [step-by-step procedure] that allowed her to measure the absolute severity of the risk or the effectiveness of warnings or of these clinical interventions. She weighed the potential costs and benets of various interventions as she monitored the risk represented by Smiths current functioning. Could Smiths statements be taken in a way to indicate to the psychologist that Brown was the target If so, the psychologist might be obligated to take steps to warn the victim or to restrain Smith through a civil commitment (although the extent of this obligation differs among various states). Smith did not provide information about what the psychologist decided or about what happened to Smith. It may seem that civil commitments are always forced or coerced, but that is not necessarily so. Some civil commitments are voluntary (that is, the patient agrees to the hospitalization); however, some voluntary hospitalizations may occur only after substantial coercion (Meyer & Weaver, 2006). This revolving door evolved because lawmakers and clinicians wanted a more humane approach to dealing with the dangerous mentally ill, by treating them in the least restrictive setting before their condition deteriorates to the point where they harm themselves or others (Hiday, 2003). Ethical and Legal Issues 735 Inpatient Commitment the MacArthur Coercion Study (MacArthur Research Network on Mental Health and the Law, 2001b) found that half of inpatients who initially reported that they didnt need hospitalization and treatment later shifted their views. The other half of the studys participants continued to believe that they didnt need hospitalization. Participants also noted that family, friends, and mental health professionals attempts to persuade them by using inducements (for example, saying that voluntarily going along with a hospitalization would give them more control over the process) did not feel like coercion, whereas attempts to persuade them by the use of force or threats (such as the threat of involuntary commitment) did feel like coercion. Moreover, patients were more likely to feel coerced when they believed that they werent allowed to tell their side of the story or when they believed that others werent acting out of concern and with respect for them. Mandated Outpatient Commitment Mandated outpatient commitment developed in the 1960s and 1970s, along with increasing deinstitutionalization of patients from mental hospitals; the goal was to develop less restrictive alternatives to inpatient care (Hiday, 2003). Such outpatient commitment may consist of legally mandated treatment that includes some type of psychotherapy, medication, or periodic monitoring of the patient by a mental health clinician. The hope is that mandated outpatient commitment will preempt a cycle observed in many patients who have been committed: (1) getting discharged from inpatient care, (2) stopping their medication, (3) becoming dangerous, and (4) ending up back in the hospital through a criminal or civil commitment or landing in jail. Researchers have investigated whether mandated outpatient commitment is effective: Are the patient and the public safer than if the patient was allowed to obtain voluntary treatment after discharge from inpatient care Does mandated treatment result in less frequent hospitalizations or incarcerations for the patient When people know that they will end up back in the hospital if they dont participate in treatment, they are more likely to comply with that treatment. That said, it is also clear that mandated outpatient commitment is not effective without adequate funding for increased therapeutic services (Perlin, 2003; Rand Corporation, 2001). The Reality of Treatment for the Chronically Mentally Ill Coercion to be hospitalized was not an issue for Andrew Goldstein. In fact, he had the opposite problem: He generally wanted to be hospitalized and tried repeatedly to make that happen. The social workers assigned to plan his release knew he shouldnt have been living on his own, and so did Goldstein, but everywhere they looked they were turned down. More than once he requested long-term hospitalization at Creedmoor, the state hospital nearby. Goldstein was instead referred to an emergency room, where he stayed overnight and was released.