Prozac

Laurence S. Baskin, MD

- Chief of Pediatric Urology

- University of California?an Francisco

- Benioff Children? Hospital San Francisco, California

Alkaline phosphatase elevated two to ve times above the baseline should raise suspicion; diagnosis is conrmed with antimitochondrial Ab reactive depression definition discount 40mg prozac with mastercard. The inability to excrete excess copper leads to deposition of the mineral in the liver depression helpline discount prozac 20 mg without prescription, brain depression zoloft cheap generic prozac canada, and other organs depression definition emedicine buy prozac 60 mg without a prescription. Patients can present with fulminant hepatitis bipolar depression 800 discount 10 mg prozac with visa, acute non fulminant hepatitis mood disorder support group cheap prozac 20mg amex, or cirrhosis, or with bizarre behavioral changes as a result of neurologic damage. Kayser-Fleischer rings develop when copper is released from the liver and deposits in Descemet membrane of the cornea. Hepatitis C is most commonly contracted through blood exposure and rarely through sexual contact. Most patients are asymptomatic until they develop complications of chronic liver disease. Treatment of cirrhotic ascites requires sodium restriction and, usually, diuretics, such as spironolactone and furosemide. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is infection of the ascitic fluid charac terized by more than 250 polymorphonuclear cells/mm3, sometimes with a positive monomicrobial culture. She has experienced similar painful episodes in the past, usually in the evening following heavy meals, but the episodes always resolved spontaneously within an hour or two. She is married, has three children, and does not drink alcohol or smoke cigarettes. On examination, she is afebrile, tachycardic with a heart rate of 104 bpm, blood pressure 115/74 mm Hg, and shallow respirations of 22 breaths per minute. She is moving uncomfortably on the stretcher, her skin is warm and diaphoretic, and she has scleral icterus. Her abdomen is soft, mildly distended with marked right upper quadrant and epigastric tenderness to palpation, hypoactive bowel sounds, and no masses or organomegaly appreciated. Her leukocyte count is 16,500/mm3 with 82% polymorphonuclear cells and 16% lymphocytes. A plain film of the abdomen shows a nonspecific gas pat tern and no pneumoperitoneum. She also has hyperbilirubinemia and an elevated alkaline phosphatase level, suggesting obstruction of the common bile duct caused by a gallstone, which is the likely cause of her pancreatitis. Considerations this 42-year-old woman complained of episodes of mild right-upper quadrant abdominal pain with heavy meals in the past. However, this episode is different in sever ity and location of pain (now radiating straight to her back and accompanied by nausea and vomiting). The elevated amylase level confirms the clinical impression of acute pancreatitis. Abdominal pain is the cardinal symptom of pancreatitis and often is severe, typically in the upper abdomen with radiation to the back. The pain often is relieved by sitting up and bending forward, and is exacerbated by food. Patients commonly experience nausea and vomiting that is precipitated by oral intake. Hemorrhagic pan creatitis with blood tracking along fascial planes would be suspected if periumbilical ecchymosis (Cullens sign) or flank ecchymosis (Grey Turners sign) is present. The most common test used to diagnose pancreatitis is an elevated serum amylase level. It is released from the inflamed pancreas within hours of the attack and remains elevated for 3 to 4 days. Amylase undergoes renal clearance, and after serum levels decline, its level remains elevated in the urine. Amylase is not specific to the pancreas, however, and can be elevated as a consequence of many other abdominal processes, such as gastrointestinal ischemia with infarction or perforation; even just the vomiting associated with pancreatitis can cause elevated amylase of salivary origin. Elevated serum lipase level, also seen in acute pancreatitis, is more specific than is amylase to pancreatic origin and remains elevated longer than does amy lase. Treatment of pancreatitis is mainly supportive and includes pancreatic rest, that is, withholding food or liquids by mouth until symptoms subside, and adequate narcotic analgesia, usually with meperidine. In patients with severe pancreatitis who sequester large volumes of fluid in their abdomen as pancreatic ascites, sometimes prodigious amounts of parenteral fluid replacement are necessary to maintain intra vascular volume. When pain has largely subsided and the patient has bowel sounds, oral clear liquids can be started and the diet advanced as tolerated. The large majority of patients with acute pancreatitis will recover spontaneously and have a relatively uncomplicated course. Several scoring systems have been developed in an attempt to identify the 15% to 25% of patients who will have a more complicated course. Pancreatic complications include a phlegmon, which is a solid mass of inflamed pancreas, often with patchy areas of necrosis. Either necrosis or a phlegmon can become secondarily infected, resulting in pancreatic abscess. Abscesses typically develop 2 to 3 weeks after the onset of illness and should be suspected if there is fever or leukocytosis. Pancreatic necrosis and abscess are the leading causes of death in patients after the first week of illness. A pancreatic pseudocyst is a cystic collection of inflammatory fluid and pancreatic secretions, which unlike true cysts do not have an epithelial lining. Most pancreatic pseudocysts resolve spontaneously within 6 weeks, especially if they are smaller than 6 cm. However, if they are causing pain, are large or expanding, or become infected, they usually require drainage. Any of these local complications of pancreatitis should be suspected if persistent pain, fever, abdominal mass, or persistent hyperamylasemia occurs. Gallstones Gallstones usually form as a consequence of precipitation of cholesterol microcrys tals in bile. When discovered incidentally, they can be followed without intervention, as only 10% of patients will develop any symp toms related to their stones within 10 years. When patients do develop symptoms because of a stone in the cystic duct or Hartmann pouch, the typical attack of biliary colic usually has a sudden onset, often precipitated by a large or fatty meal, with severe steady pain in the right-upper quadrant or epigastrium, lasting between 1 and 4 hours. They may have mild elevations of the alkaline phosphatase level and slight hyperbilirubinemia, but elevations of the bilirubin level over 3 g/dL suggest a common duct stone. The first diagnostic test in a patient with suspected gallstones usually is an ultrasonogram. The test is noninvasive and very sensitive for detect ing stones in the gallbladder as well as intrahepatic or extrahepatic biliary duct dilation. One of the most common complications of gallstones is acute cholecystitis, which occurs when a stone becomes impacted in the cystic duct, and edema and inflammation develop behind the obstruction. This is apparent ultrasonographically as gallbladder wall thickening and pericholecystic fluid, and is characterized clini cally as a persistent right-upper quadrant abdominal pain, with fever and leukocytosis. Cultures of bile in the gallbladder often yield enteric flora such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella. The positive test shows visu alization of the liver by the isotope, but nonvisualization of the gallbladder may indicate an obstructed cystic duct. This patient with fever, right-upper quadrant pain, and a history of gallstones likely has acute cholecystitis. A pancreatic pseudocyst has a clinical presentation of abdominal pain and mass and persistent hyperamylasemia in a patient with prior pancreatitis. Acute pancreatitis usually is managed with pancreatic rest, intravenous hydration, and analgesia, often with narcotics. Patients with pancreatitis who have zero to two of the Ranson criteria are expected to have a mild course; those with three or more criteria can have significant mortality. Pancreatic complications (phlegmon, necrosis, abscess, pseudocyst) should be suspected if persistent pain, fever, abdominal mass, or persistent hyper amylasemia occurs. Patients with asymptomatic gallstones do not require treatment; they can be observed and treated if symptoms develop. Cholecystectomy is performed for patients with symptoms of biliary colic or for those with complications. Acute cholecystitis is best treated with antibiotics and then cholecystectomy, generally within 48 to 72 hours. Initial management of acute pancreatitis: critical issues during the first 72 hours. His wife, who witnessed the episode, reports that he was unconscious for approximately 2 or 3 minutes. When he awakened, he was groggy for another minute or two, and then seemed himself. This has never happened to him before, but his wife does report that for the last several months he has had to curtail activities, such as mowing the lawn, because he becomes weak and feels light-headed. His only medical history is osteoarthritis of his knees, for which he takes acetaminophen. He is afebrile, his heart rate is regular at 35 bpm, and his blood pressure is 118/72 mm Hg, which remains unchanged on standing. His chest is clear to auscultation, and his heart rhythm is regu lar but bradycardic with a nondisplaced apical impulse. Laboratory examination shows normal blood counts, renal function, and serum electrolyte levels, and negative cardiac enzymes. He has experienced decreasing exercise tolerance recently because of weakness and presyncopal symptoms. He should be evaluated for myocardial infarc tion and structural cardiac abnormalities. If this evaluation is negative, he may sim ply have conduction system disease as a consequence of aging. The causes are varied, but they all result in transiently diminished cerebral perfusion leading to loss of consciousness. The prog nosis is quite varied, ranging from a benign episode in an otherwise young, healthy person with a clear precipitating event, such as emotional stress, to a more serious occurrence in an older patient with cardiac disease. In the latter situation, syncope has been referred to as sudden cardiac death, averted. Traditionally, the etiologies of syncope have been divided into neurologic and car diac. However, this probably is not a useful classification, because neurologic diseases are uncommon causes of syncopal episodes. Vertebrobasilar insufficiency with resultant loss of consciousness is often discussed yet rarely seen in clinical practice. Seizure episodes are a common cause of transient loss of consciousness, and distin guishing seizure episodes from syncopal episodes based on history often is quite diffi cult. Loss of consciousness associated with seizure typically lasts longer than 5 minutes, with a prolonged postictal period, whereas patients with syncope usually become reori ented quickly. To further complicate matters, the same lack of cerebral blood flow that produced the loss of consciousness can lead to postsyncopal seizure activity. Seizures are best discussed elsewhere, so our discussion here is confined to syncope. The only neurologic diseases that commonly cause syncope are disturbances in autonomic function leading to orthostatic hypotension as occurs in diabetes, parkinsonism, or idiopathic dysautonomia. By far, the most useful evaluation for diagnosing the cause of syncope is the patients history. Because, by definition, the patient was unconscious, the patient may only be able to report preceding and subsequent symptoms, so finding a witness to describe the episode is extremely helpful. Vasovagal syncope refers to excessive vagal tone causing impaired autonomic responses, that is, a fall in blood pressure without appropriate rise in heart rate or vasomotor tone. This is, by far, the most common cause of syncope and is the usual cause of a fainting spell in an otherwise healthy young person. Episodes often are precipitated by physical or emotional stress, or by a painful experience. There is usu ally a clear precipitating event by history and, often, prodromal symptoms such as nausea, yawning, or diaphoresis. Syncopal episodes also can be triggered by physiologic activi ties that increase vagal tone, such as micturition, defecation, or coughing in other wise healthy people. Less commonly, carotid sinus pressure can cause a fall in arterial pressure without cardiac slowing. When recurrent syncope as a result of bradyarrhythmias occurs, a demand pacemaker is often required. Patients with orthostatic hypotension typically report symptoms related to posi tional changes, such as rising from a seated or recumbent position, and the postural drop in systolic blood pressure by more than 20 mm Hg can be demonstrated on examination. This can occur because of hypovolemia (hemorrhage, anemia, diarrhea or vomiting, Addison disease) or with adequate circulating volume but impaired autonomic responses. It also can be caused by autonomic insufficiency seen in diabetic neuropathy, in a syndrome of chronic idiopathic orthostatic hypotension in older men, or the primary neurologic conditions mentioned previously. Multiple events that all are unwitnessed (not corroborated) or that occur only in periods of emo tional upset suggest factitious symptoms. Etiologies of cardiogenic syncope include rhythm disturbances and structural heart abnormalities. Certain structural heart abnormalities will cause obstruction of blood flow to the brain, resulting in syncope. Syncope due to cardiac outflow obstruction can also occur with massive pulmonary embolism and severe pulmonary hypertension.

History is an important diagnostic step: blood-streaked purulent sputum suggests bronchitis; chronic copious sputum production suggests bron chiectasis anxiety in toddlers prozac 10mg with visa. Hemoptysis with an acute onset of pleuritic chest pain and dyspnea suggests a pulmonary embolism anxiety ebola order prozac discount. If the chest imaging reveals a pulmonary mass anxiety 5 months postpartum cheap prozac 20mg line, the patient should undergo fiberoptic bronchoscopy to localize the site of bleeding and to visualize and attempt to biopsy any endobronchial lesion depression symptoms examples buy 10mg prozac with visa. Patients with massive hemoptysis require measures to maintain their airway and to prevent spilling blood into unaf fected areas of the lungs depression definition medical dictionary purchase prozac 10 mg with amex. If the bleeding is localized to one lung anxiety chat rooms order 10 mg prozac otc, the affected side should be placed in a dependent position so that bleeding does not flow into the contralateral side. They may also require endotracheal intubation and rigid bronchoscopy for better airway control and suction capacity. Risk Factors for Lung Cancer Primary lung cancer, or bronchogenic carcinoma, is the leading cause of cancer deaths in both men and women. Of the 15% of lung cancers that are not related to smoking, the majority are found in women for reasons that are unknown. Thoracic radiation exposure as well as exposure to environmental toxins such as asbestos or radon are also associated with increased risk of developing lung cancer. Clinical Presentation of Lung Cancer Only 5% to 15% of patients with lung cancer are asymptomatic when diagnosed. Chest pain is also a possible symptom of lung cancer and suggests pleural involvement or neoplastic invasion of the chest wall. Horner syndrome is caused by the invasion of the cervicothoracic sympathetic nerves and occurs with apical tumors (Pancoast tumor). Once a patient presents with symptoms or radiographic findings suggestive of lung cancer, the next steps are as follows: 1. It usually is a central/hilar lesion with local extension that may present with symptoms caused by bronchial obstruction, such as atelectasis and pneumonia. It may present on chest x-ray as a cavitary lesion; squamous cell cancer is by far the most likely to cavitate. Adenocarcinoma has the least association with smoking and a stronger associa tion with pulmonary scars/fibrosis. Small cell cancer, previously called oat-cell, is made up of poorly differentiated cells of neuroendocrine origin. Eighty percent of patients have metastasis at the time of diagnosis, so its treatment usually is different from that of other lung cancers. General Principles of Treatment Treatment of lung cancer consists of surgical resection, chemotherapy, and/or radia tion therapy in different combinations, depending on the tissue type and extent of the disease, and may be performed with either curative or palliative intent. It is staged as either limited-stage disease, that is, disease confined to one hemithorax that can be treated within a radiotherapy port, or extensive-stage disease, that is, contralateral lung involvement or distant metastases. With treatment, survival can be prolonged, and approximately 20% to 30% of patients with limited-stage disease can be cured with radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Because most lung cancer occurs in older patients who have been smokers, they frequently have underlying cardiopulmonary disease and require preoperative evaluation, including pulmonary function testing, to predict whether they have sufficient pulmonary reserve to tolerate a lobectomy or pneumonectomy. Solitary Pulmonary Nodulethe solitary pulmonary nodule is defined as a nodule surrounded by normal parenchyma. The large majority of incidentally discovered nodules are benign, but differentiation between benign etiologies and early-stage malignancy can be challenging. Proper management of a solitary nodule in an individual patient depends on a variety of elements: age, risk factors, presence of calcifications, and size of the nodule. The presence and type of calcification on a solitary pulmonary nodule can be helpful. Radiographic stability for 2 years or longer is strong evidence of benign etiology. Pulmonary function testing to evaluate pulmonary reserve to evaluate for pulmonectomy. Initiate palliative radiation because the patient is not a candidate for cura tive resection. Urgent diagnosis and treatment are mandatory because of impaired cerebral venous drainage and resultant increased intracranial pressure or possibly fatal intracranial venous thrombosis. Angioedema, hypothyroidism, and trichinosis all may cause facial swelling, but not the plethora or swelling of the arm. This suggests an intrathoracic mass causing bronchial obstruction and impairment of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, causing vocal cord paralysis. Ninety percent of patients with lung cancer of all histologic types have a smoking history. The most common form of lung cancer found in nonsmokers, young patients, and women is adenocarcinoma. Tissue diagnosis is essential for proper treatment of any malignancy and should always be the rst step. Once a specic tissue diagnosis is obtained, the cancer is staged for prognosis and to guide therapy: is the cancer poten tially resectable Questions for this patient include the tissue type, location of spread, and whether the pleural effusion is caused by malignancy. A solitary pulmonary nodule measuring 8 mm or less can be followed radiographically. For larger lesions, a biopsy, whether bronchoscopic, per cutaneous, or surgical, should be considered. Steps in management of a patient with suspected lung cancer include tissue diagnosis, staging, preoperative evaluation, and treatment with surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy. Small cell lung cancer usually is metastatic at the time of diagnosis and not resectable. He was in his usual state of good health until 1 week ago, when he developed mild nasal congestion and achiness. He otherwise felt well until last night, when he became fatigued and feverish, and developed a cough associated with right-sided pleuritic chest pain. His physical examination is unremarkable except for bronchial breath sounds and end-inspiratory crackles in the right lower lung field. His physical examination is unremarkable except for bronchial breath sounds and end-inspiratory crackles in the right lower lung field, and there is a right lower lobe consolidation on chest x-ray. Know the causative organisms in community-acquired pneumonia and the appropriate therapeutic regimens. Discuss the role of radiologic and laboratory evaluation in the diagnosis of pneumonia. Understand the difference between aspiration pneumonitis and aspiration pneumonia. Considerations this previously healthy 44-year-old man has clinical and radiographic evidence of a focal consolidation of the lungs, which is consistent with a bacterial process, such as infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. The specific causative organism is usu ally not definitively established, so you will need to initiate empiric antimicrobial therapy and risk stratify the patient to determine whether he can safely be treated as an outpatient or requires hospitalization. Patients may present with any of a combination of cough, fever, pleuritic chest pain, sputum production, shortness of breath, hypoxia, and respiratory distress. Certain clinical presentations are associ ated with particular infectious agents. For example, the typical pneumonia is often described as having a sudden onset of fever, cough with productive sputum, often associated with pleuritic chest pain, and possibly rust-colored sputum. The atypical pneumonia is char acterized as having a more insidious onset, with a dry cough, prominent extrapul monary symptoms such as headache, myalgias, sore throat, and a chest radiograph that appears much worse than the auscultatory findings. Although these characterizations are of some diagnostic value, it is very difficult to reliably distinguish between typi cal and atypical organisms based on clinical history and physical examination as the cause of a specific patients pneumonia. Therefore, pneumonias are typically classi fied according to the immune status of the host, the radiographic findings, and the setting in which the infection was acquired, in an attempt to identify the most likely causative organisms and to guide initial empiric therapy. Community-acquired pneumonia, as opposed to nosocomial or hospital-acquired pneumonia, is most commonly caused by S pneumoniae, M pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, or respiratory viruses, such as influenza and adenovirus. Despite careful history and physical and routine lab and radiographic investigation, it is difficult to determine a specific pathogen in most cases. Epide miology and risk factors may provide some clues: Chlamydia psittaci (bird exposure), coccidiomycosis (travel to the American southwest), or histoplasmosis (endemic to the Mississippi Valley) may be the cause. Although outpatients usually are diagnosed and empiric treatment is begun based on clinical findings, further diagnostic evaluation is important in hospitalized patients. Chest radiography is important to try to define the cause and extent of the pneumonia and to look for complications, such as parapneumonic effusion or lung abscess. Unless the patient cannot mount an immune response, as in severe neutropenia, or the process is very early, every patient with pneumonia will have a visible pulmonary infiltrate. Infection with S pneumoniae classically presents with a dense lobar infiltrate, often with an associated para pneumonic effusion. Diffuse interstitial infiltrates are common in Pneumocystis pneumonia and viral processes. Appearance of cavitation suggests a necrotizing infection such as Staphylococcus aureus, tuberculosis, or gram-negative organisms such as Klebsiella pneumoniae. Serial chest radiography of inpatients usually is unnecessary, because many weeks are required for the infiltrate to resolve; serial chest radiography typically is performed if the patient does not show clinical improvement, has a pleural effusion, or has a necrotizing infection. Microbiologic studies, such as sputum Gram stain and culture, and blood cultures are important to try to identify the specific etiologic agent causing the illness. How ever, use of sputum Gram stain and culture is limited by the frequent contamination by upper respiratory flora as the specimen is expectorated. However, if the sputum appears purulent and it is minimally contaminated (>25 polymorphonuclear cells and <10 epithelial cells per low-power field), the diagnostic yield is good. Addition ally, blood cultures can be helpful, because 30% to 40% of patients with pneumo coccal pneumonias are bacteremic. Serologic studies can be performed to diagnose patients who are infected with organisms not easily cultured, for example, Legionella, Mycoplasma, or C pneumoniae. Initially, empiric treatment is based upon the most common organisms given the clinical scenario. For outpatient therapy of community-acquired pneumonia, macrolide antibiotics, such as azithromycin, or antipneumococcal quinolones, such as moxifloxacin or levofloxacin, are good choices for treatment of S pneumoniae, Mycoplasma, and other common organisms. Hospitalized patients with community acquired pneumonia usually are treated with an intravenous third-generation cephalosporin plus a macrolide or with an antipneumococcal quinolone. For immu nocompetent patients with hospital-acquired or ventilator-associated pneumonias, the causes include any of the organisms that can cause community-acquired pneumonia, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, or S aureus, as well as more gram-negative enteric bacteria and oral anaerobes. Accordingly, the initial antibiotic coverage is broader and includes an antipseudomonal beta-lactam, such as piperacillin or cefepime, plus an aminoglycoside. Aspiration pneumonitis is a chemical injury to the lungs caused by aspira tion of acidic gastric contents into the lungs. Because of the high acidity, gastric contents are normally sterile, so this is not an infectious process but rather a chemi cal burn that causes a severe inflammatory response, which is proportional to the volume of the aspirate and the degree of acidity. This inflammatory response can be profound and produce respiratory distress and a pulmonary infiltrate that is appar ent within 4 to 6 hours and typically resolves within 48 hours. Aspiration of gastric contents is most likely to occur in patients with a depressed level of consciousness, such as those under anesthesia or suffering from a drug overdose, intoxication, or after a seizure. Aspiration pneumonia, by contrast, is an infectious process caused by inha lation of oropharyngeal secretions that are colonized by bacterial pathogens. It should be noted that many healthy adults frequently aspirate small volumes of oropharyngeal secretions while sleeping (this is the primary way that bacteria gain entry to the lungs), but usually the material is cleared by coughing, ciliary transport, or normal immune defenses so that no clinical infection results. How ever, any process that increases the volume or bacterial organism burden of the secretion or impairs the normal defense mechanisms can produce clinically appar ent pneumonia. This is most commonly seen in elderly patients with dysphagia, such as stroke victims, who may aspirate significant volumes of oral secretions, and those with poor dental care. The affected lobe of the lung depends upon the patients position: in recumbent patients, the posterior segments of the upper lobes and apical segments of the lower lobes are most common. In contrast to aspiration pneumonitis, where aspiration of vomitus may be witnessed, the aspiration of oral secretions typically is silent and should be suspected when any institutionalized patient with dysphagia presents with respiratory symptoms and pulmonary infil trate in a dependent segment of the lung. Treatment for aspiration pneumonitis, because it usually is not infectious, is mainly supportive. Antibiotics are often added if secondary bacterial infection is suspected because of failure to improve within 48 hours, or if the gastric contents are suspected to be colonized because of acid suppression or bowel obstruction. The illness began 1 week ago with fever, muscle aches, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, with nonproductive cough developing later that week and rapidly becoming worse. Therapy for which of the follow ing atypical organisms must be considered in this case Legionella typically presents with myalgias, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and severe pneumonia. This nursing home resident would be considered to have a nosocomial rather than community-acquired infection, with a higher incidence of gram negative infection. Her age and comorbid medical conditions place her at high risk, requiring hospitalization for intravenous antibiotics such as a third generation cephalosporin. Antibiotic therapy is generally not indicated for aspiration pneumonitis, but patients need to be observed for clinical deterioration. Therefore, diagnosis and empiric treatment of pneumonia are based upon the setting in which it was acquired (community acquired or health-care associated) and the immune status of the host. Clinical criteria, such as patient age, vital signs, mental status, and renal function, can be used to risk stratify patients with pneumonia to decide who can be treated as an outpatient and who requires hospitalization.

Generic 20 mg prozac visa. Be a Lonely Introvert or a Depressed Failure of an Extrovert?.

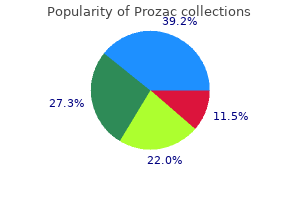

Dual mechanism hypothesis Remission rates are higher with antidepressants or with combinations of antidepressants having dual serotonin and norepinephrine actions depression symptoms of pregnancy prozac 10mg discount, as compared with those having serotonin selective actions anxiety medication 05 mg order generic prozac line. Corollary: Patients unresponsive to a single-action agent may respond mood disorder other dis cheap prozac generic, and eventually remit depression young living buy prozac overnight, with dual-action strategies anxiety of influence buy prozac us. Data are increasingly showing that the percentage of patients who remit is higher for antidepressants or combinations of antidepressants acting synergistically on both serotonin and norepinephrine than for those acting just on serotonin alone depression symptoms dysthymia buy prozac 60 mg with visa. Exploiting this strategy may help increase the number of remitters, prevent or treat more cases of poop out, and convert treatment-refractory cases into successful outcomes. It is potentially important to treat symptoms of depression "until they are gone" for reasons other than the obvious reduction of current suffering. Depression may be part of an emerging theme for many psychiatric disorders today, namely, that uncontrolled symptoms may indicate some ongoing pathophysiological mechanism in the brain, which if allowed to persist untreated may cause the ultimate outcome of illness to be worse. Depression may thus have a long-lasting or even irreversible neuropathological effect on the brain, rendering treatment less effective if symptoms are allowed to progress than if they are removed by appropriate treatment early in the course of the illness. In summary, the natural history of depression indicates that this is a life-long illness, which is likely to relapse within several months of an index episode, especially if untreated or under-treated or if antidepressants are discontinued, and is prone to multiple recurrences that are possibly preventable by long-term antide Depression and Bipolar Disorders 153 pressant treatment. Antidepressant response rates are high, but remission rates are disappointingly low unless mere response is recognized and targeted for aggressive management, possibly by single drugs or combinations of drugs with dual serotonin norepinephrine pharmacological mechanisms when selective agents are not fully effective. Longitudinal Treatment of Bipolar Disorderthe mood stabilizer lithium was developed as the first treatment for bipolar disorder. It has definitely modified the long-term outcome of bipolar disorder because it not only treats acute episodes of mania, but it is the first psychotropic drug proven to have a prophylactic effect in preventing future episodes of illness. Lithium even treats depression in bipolar patients, although it is not so clear that it is a powerful antidepressant for unipolar depression. Nevertheless, it is used to augment antide pressants for treating resistant cases of unipolar depression. Other mood stabilizers are arising from the group of drugs that were first developed as anticonvulsants and have also found an important place in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Several anticonvulsants are especially useful for the manic, mixed, and rapid cycling types of bipolar patients and perhaps for the depressive phase of this illness as well. An-tipsychotics, especially the newer atypical antipsychotics, are also useful in the treatment of bipolar disorders. When given with lithium or other mood stabilizers, they may reduce depressive episodes. Interestingly, however, antidepressants can flip a depressed bipolar patient into mania, into mixed mania with depression, or into chaotic rapid cycling every few days or hours, especially in the absence of mood stabilizers. Thus, many patients with bipolar disorders require clever mixing of mood stabilizers and antidepressants, or even avoidance of antidepressants, in order to attain the best outcome. Without consistent long-term treatment, bipolar disorders are potentially very disruptive. Patients often experience a chronic and chaotic course, in and out of the hospital, with psychotic episodes and relapses. There is a significant concern that intermittent use of mood stabilizers, poor compliance, and increasing numbers of episodes will lead to even more episodes of bipolar disorder, and with less responsiveness to lithium. Thus, stabilizing bipolar disorders with mood stabilizers, atypical antipsychotics, and antidepressants is increasingly important not only in returning these patients to wellness but in preventing unfavorable long-term outcomes. Despite classical psychoanalytic notions suggesting that children do not become depressed, recent evidence is quite to the contrary. Unfortunately, very little controlled research has been done on the use of antidepressants to treat depression in children, so no antidepressant is currently approved for treatment of depression in children. However, many of the newer antidepressants have been extensively tested in children with other conditions. For example, some antidepressants are approved 154 Essential Psychopharmacology for the treatment of children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Thus, the safety of some antidepressants is well established in children even if their efficacy for depression is not. Nevertheless, antidepressant treatment studies in children are in progress, and extensive anecdotal observations suggest that antidepressants, particularly the newer, safer ones (see Chapters 6 and 7), are in fact useful for treating depressed children. Thankfully, this is now providing incentives for doing the research necessary to prove the safety and efficacy of antidepressants to treat depression in children, a long neglected area of psychopharmacology. Mania and mixed mania have not only been greatly underdiagnosed in children in the past but also have been frequently misdiagnosed as attention deficit disorder and hyper activity. Furthermore, bipolar disorder misdiagnosed as attention deficit disorder and treated with stimulants can produce the same chaos and rapid cycling state as antidepressants can in bipolar disorder. Thus, it is important to consider the diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children, especially those unresponsive or apparently worsened by stimulants and those who have a family member with bipolar disorder. These children may need their stimulants and antidepressants discontinued and treatment with mood stabilizers such as valproic acid or lithium initiated. Documentation of the safety and efficacy of antidepressants and mood stabilizers is better for adolescents than for children, although not at the standard for adults. That is unfortunate, because mood disorders often have their onset in adolescence, especially in girls. Not only do mood disorders frequently begin after puberty, but children with onset of a mood disorder prior to puberty often experience an exacerbation in adolescence. Synaptic restructuring dramatically increases after age 6 and throughout adolescence. Such events may explain the dramatic rise in the incidence of the onset of mood disorders, as well as the exacerbation of preexisting mood disorders, during adolescence. Unfortunately, mood disorders are frequently not diagnosed in adolescents, especially if they are associated with delinquent antisocial behavior or drug abuse. This is indeed unfortunate, as the opportunity to stabilize the disorder early in its course and possibly even to prevent adverse long-term outcomes associated with lack of adequate treatment can be lost if mood disorders are not aggressively diagnosed and treated in adolescence. The modern psychopharmacologist should have a high index of suspicion and increased vigilance to the presence of a mood disorder in adolescents, because treatments may well be just as effective in adolescents as they are in adults and perhaps more critical to preserve normal development of the individual. According to the monoamine hypothesis, in the case of depression the neurotransmitter is depleted, causing neurotransmitter deficiency. This accumulation theoretically reverses the prior neurotransmitter deficiency (see. Tricyclic antidepressants exert their antidepressant action by blocking the neurotransmitter reuptake pump, thus causing neurotransmitter to accumulate. This accumulation, according to the monoamine hypothesis, reverses the prior neurotransmitter deficiency (see. The tricyclic antidepressants also increased the monoamine neurotransmitters, resulting in relief from depression due to blockade of the monoamine transport pumps. Although the monoamine hypothesis is obviously an overly simplified notion about depression, it has been very valuable in focusing attention on the three monoamine neurotransmitter systems norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin. This has led to a much better understanding of the physiological functioning of these three neurotransmitters and especially of the various mechanisms by which all known antidepressants act to boost neurotransmission at one or more of these three monoamine neurotransmitter systems. Monoaminergic Neurons In order to understand the monoamine hypothesis, it is necessary first to understand the normal physiological functioning of monoaminergic neurons. Monoamine neurotransmitters are synthesized by means of enzymes, which assemble neurotransmitters in the cell body or nerve terminal. These differences can be exploited by drugs so that the transport of one monoamine can be blocked independently of another. More recently, adrenergic receptors have been even further subclassified on the basis of both pharmacologic and molecular differences. On the other hand, alpha 2 receptors are the only presynaptic noradrenergic receptors on noradrenergic neurons. Presynaptic alpha 2 re ceptors are important because both the terminal and the somatodendritic re-ceptors are autoreceptors. They are located either on the axon terminal, where they are called terminal alpha 2 receptors, or at the cell body (soma) and nearby dendrites, where they are called somatodendritic alpha 2 receptors. The principal function of the locus coeruleus is to determine whether attention is being focused on the external environment or on monitoring the internal milieu of the body. It helps to prioritize competing incoming stimuli and fixes attention on just a few of these. Thus, one can either react to a threat from the environment or to signals such as pain coming from the body. Where one is paying attention will determine what one learns and what memories are formed as well. Malfunction of the locus coeruleus is hypothesized to underlie disorders in which mood and cognition intersect, such as depression, anxiety, and disorders of attention and information processing. There are many specific noradrenergic pathways in the brain, each mediating a different physiological function. Different receptors may mediate these differential effects of norepinephrine in frontal cortex, postsynaptic beta 1 receptors for mood. The projection from the locus coeruleus to limbic cortex may regulate emotions, as well as energy, fatigue, and psychomotor agitation or psychomotor retardation. A projection to the cerebellum may regulate motor movements, especially tremor. Norepinephrine from sympathetic neurons leaving the spinal cord to innervate peripheral tissues control heart rate. A plethora of dopamine receptors exist, including at least five pharmacological subtypes and several more molecular isoforms. Dopamine 1, 2, 3, and 4 receptors are all blocked by some atypical antipsychotic drugs, but it is not clear to what extent dopamine 1, 3, or 4 receptors contribute to the clinical properties of these drugs. They provide negative feedback input, or a braking action on the release of dopamine from the presynaptic neuron. Most of the cell bodies for noradrenergic neurons in the brain are located in the brainstem in an area known as the locus coeruleus. This is the headquarters for most of the important noradrenergic pathways mediating behavior and other functions such as cognition, mood, emotions, and movements. Some noradrenergic projections from the locus coeruleus to frontal cortex are thought to be responsible for the regulatory actions of norepinephrine on mood. Beta 1 postsynaptic receptors may be important in transducing noradrenergic signals regulating mood in postsynaptic targets. Other noradrenergic projections from the locus coeruleus to frontal cortex are thought to mediate the effects of norepinephrine on attention, concentration, and other cognitive functions, such as working memory and the speed of information processing. Alpha 2 postsynaptic receptors may be important in transducing postsynaptic signals regulating attention in postsynaptic target neurons. The noradrenergic projection from the locus coeruleus to limbic cortex may mediate emotions, as well as energy, fatigue, and psychomotor agitation or psychomotor retardation. The noradrenergic projection from the locus coeruleus to the cerebellum may mediate motor movements, especially tremor. Noradrenergic innervation of the heart via sympathic neurons leaving the spinal cord regulates cardiovascular function, including heart rate, via beta 1 receptors. Noradrenergic innervation of the urinary tract via sympathetic neurons leaving the spinal cord regulates bladder emptying via alpha 1 receptors. The tryptophan transport pump is distinct from the serotonin transporter (see. Serotonin is then stored in synaptic vesicles, where it stays until released by a neuronal impulse. This organization allows serotonin release to be controlled not only by serotonin but also by norepinephrine, even though the serotonin neuron does not itself release nor epinephrine. They convey messages from the presynaptic serotonergic neuron to the target cell postsynaptically. Shown here are the alpha 2 presynaptic heteroreceptors on serotonin axon terminals. The serotonin neuron not only has serotonin receptors located presynaptically, but also has presynaptic noradrenergic receptors that regulate serotonin release. On the axon terminal of serotonergic receptors are located presynaptic alpha 2 receptors. When norepinephrine is released from nearby noradrenergic neurons, it can diffuse to alpha 2 receptors, not only to those on noradrenergic neurons but also to the same receptors on serotonin neurons. Like its actions on noradrenergic neurons, norepinephrine occupancy of alpha 2 receptors on serotonin neurons will turn off serotonin release. Alpha 2 receptors on a norepinephrine neuron are called autoreceptors, but alpha 2 receptors on serotonin neurons are called heteroreceptors. Another type of presynaptic norepinephrine receptor on serotonin neurons is the alpha 1 receptor, located on the cell bodies. Thus, norepinephrine can act as both an accelerator and a brake for serotonin release (Table 5-22 and. The headquarters for the cell bodies of serotonergic neurons is in the brainstem area called the raphe nucleus. This figure shows how norepinephrine can function as a brake for serotonin release. When norepinephrine is released from nearby noradrenergic neurons, it can diffuse to alpha 2 receptors, not only to those on noradrenergic neurons but as shown here, also to these same receptors on serotonin neurons. Thus, serotonin release can be inhibited not only by serotonin but, as shown here, also by norepinephrine.

In cases of preseptal (periorbital) cellulitis depression trigger definition cheap prozac amex, the remainder of the eye exam is normal mood disorder zoloft order generic prozac line. The presence of proptosis depression symptoms loss of balance buy online prozac, chemosis extraocular muscle limitation depression market definition buy prozac 20 mg line, diplopia depression test bipolar buy discount prozac on-line, or decreased visual acuity suggests orbital cellulitis or subperiosteal abscess depression definition psychology cheap 10 mg prozac free shipping. With cavernous thrombosis or intracranial extension, findings may include a frozen globe (ophthalmoplegia), papilledema, blindness, meningeal signs, or neurologic deficits secondary to brain abscess or cerebritis. Superior orbital fissure syndrome is a symptom complex consisting of retroorbital pain, paralysis of extraocular muscles, and impairment of first trigeminal branches. This is most often a result of trauma involving fracture at the superior orbital fissure, but dysfunction of these structures can arise secondary to compres sion. A subperiosteal abscess is identifiable as a lentiform, rim-enhancing hypodense collection in the medial orbit with adjacent sinusitis. In the absence of abscess formation, there may be orbital fat stranding, solid enhancing phlegmon, or swollen and enhancing extraocular muscles, consistent with orbital cel lulitis. Pathology In younger children, microbiology is often single aerobes including alphaStrep tococcus, Haemophilus influenzae, o r c o a g u l a s e p o s i t i v e Staphylococcus. Clearly, surgical drainage is required urgently for abscess formation or decreased visual acuity. If there is any progression or lack of resolution with medical therapy over 48 hours, surgery is recommended. Surgical drainage may be accomplished endoscopically by experienced surgeons; however, consent for an external ethmoidectomy approach is recommended. Regardless of approach, the abscess should be drained and the underlying sinus disease should be ad dressed. For cavernous thrombosis, involved sinuses including the sphenoid must be drained; systemic anticoagulation remains controversial. N Outcome and Follow-Upthe natural history of untreated disease (all stages) results in blindness in at least 10%. There remains up to an 80% mortality rate with cavernous sinus involvement, although new literature reports suggest this figure is high. G Management requires a multidisciplinary approach including neurosurgical consultation. G Complications include meningitis, dural sinus thrombosis, and intracranial abscess. The frontal sinus is commonly the source, although ethmoid or sphenoid sinusitis can lead to in tracranial spread. Complications include meningitis, epidural abscess, subdural abscess, parenchymal brain abscess, and cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis. Currently, probably less than 1% of sinusitus cases are complicated by spread of infection. N Clinical Signs and Symptomsthe p a t i e n t w i t h m e n i n g i t i s o f a r h i n o l o g i c o r i g i n w i l l m a n i f e s t s i g n s a n d s y m p toms typical of bacterial meningitis. These include high fever, photophobia, nausea and emesis, mental status change, and nuchal rigidity, pulse and blood pressure changes. A pa renchymal brain abscess of rhinologic origin (frontal lobe abscess) may initially result in few signs or symptoms. However, this may progress from headache to signs of increased intracranial pressure, vomiting, papilledema, confusion, somnolence, bradycardia, and coma. Cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis re sults in spiking fevers, chills, proptosis, chemosis, decreased visual acuity and blindness, and extraocular muscle paresis. Infection can rapidly spread to the contralateral cavernous sinus via venous communications. The incidental finding of paranasal sinus disease on imaging does not necessarily signify a causal relationship. Also, traumatic bone disruption may allow commu nication of infected sinus contents with dura, for example, after posterior table fracture of the frontal sinus. Also, infection may propagate via venous channels in bone or retrograde venous circulation to the cavernous sinus. General hematogenous spread is possible, especially in a severely immuno compromised host. Physical Exam Complete head and neck exam is required with careful assessment of all cranial nerves. Nasal endoscopy may reveal active sinonasal disease and provide mu copus for culture and sensitivities. A neurologic exam including orientation to person, place, and date will reveal any focal deficits and serve as a useful baseline to monitor for any deterioration. The presence of ocular findings or neurologic deficit should prompt ophthalmologic and neurosurgical consultations. Cell count (tube 3), protein and glucose (tube 2), and Gram stain with culture and sensitivities (tube 1) are ordered. Vancomycin is often added for 224 Handbook of OtolaryngologyHead and Neck Surgery Table 3. The role for anticoagulation for cavernous thrombophlebitis remains controversial. Anticoagulation may interfere with the ability to perform intracranial pressure monitoring or craniotomy. Surgicalthe underlying sinus infection is drained either by endoscopic or open approach. If an intracranial abscess is present, this is drained by the neuro surgeon in conjunction with sinus drainage. Gthe skull base can be repaired with endoscopic instruments from below, or via neurosurgical approach from above. The underlying problem may be the result of trauma, iatrogenic injury, or congenital anomaly, or it may arise spontaneously with no obvious specific cause. Although the exact incidence of complications is unclear currently, previous estimates suggest a! N Clinical Signs and Symptoms P a t i e n t s p r e s e n t w i t h w a t e r y r h i n o r r h e a. O f t e n, t h e d r a i n a g e c a n b e p r o v o k e d by leaning the patient forward with the head lowered. Anosmia and nasal congestion may accompany iatrogenic skull base injury with encephalocele. Vasomotor rhinitis typically is elicited by cold temperatures, physical activity, or other specific stimuli. N Evaluation Historythe approach to the patient typically begins with a thorough and complete history. A source of skull base damage may, of course, be quite obvious if there was a suspected iatrogenic injury during preceding endoscopic 226 Handbook of OtolaryngologyHead and Neck Surgery ethmoid surgery. One should note if the drainage is unilateral as well as its duration and severity. Associated complaints such as headache, visual disturbance, epistaxis, and anosmia should be noted. Details of any previous sinonasal surgery, neurosurgery, otologic surgery, or trauma are important. If the injury is iatrogenic, it may be possible to assess the location and size of the skull base defect. Be suspicious of any mass arising medial to the middle turbinate, as encephalocele or esthesioneuroblastoma can arise in this location. Having the patient perform the Valsalva maneuver may result in visible enlargement of a meningocele or encephalocele. Imaging Identification of the site of leak may be straightforward or may be difficult. This scan should be obtained using an image-guidance protocol so that computer-assisted surgical navigation can be used for endoscopic repair. Labs If rhinorrhea fluid can be collected, this should be sent for "-2 transferrin assay. Usually, at least 1 mL is required; the laboratory may require refrig eration or rapid handling of the specimen. Radioactive Pledget Scanning this study can be done to help confirm and localize a leak site. Small cotton oid 1 # 3 neuropledgets can be trimmed and placed within the nasal cavity in defined locations. Usually, two pledgets are placed per nostril, one ante riorly and one posteriorly, with the string secured to the skin and labeled. After suitable time, the pledgets are removed and assayed for radio activity counts. Intrathecal fluorescein can cause seizures at higher dosage; however, the protocol described here is widely accepted as safe. N Treatment Options S k u l l b a s e d i s r u p t i o n c a u s i n g C S F r h i n o r r h e a i s m a n a g e d w i t h s u r g i c a l r e p a i r. Repair of Acute Iatrogenic Injury If the ethmoid roof is injured during sinus surgery, it may be possible to repair the injury. If there is extensive injury, severe bleeding, or obvious intradural injury, it is highly recommended that neurosurgical consultation be obtained, if possible. Concomitant injury to the anterior ethmoid artery can occur, so the orbit should be assessed for lid edema, ecchymosis, and proptosis. If possible, a bone graft placed 228 Handbook of OtolaryngologyHead and Neck Surgery i n t r a c r a n i a l l y i s u s e d. After placing the bone on the intracranial side of the defect, fibrin glue (or similar material) and fascia or other soft tissue is layered on the nasal side of the defect, followed by several layers of absorbable packing material such as Gelfoam. It is helpful if the patient can emerge from anesthesia smoothly, without buckingand straining, and without the need for high-pressure bag-mask ventilation fol lowing extubation, to minimize chances of causing pneumocephalus. If the scan reveals hematoma or significant pneumocephalus, neurosurgical consultation is necessary. Otherwise, post operative management should include head of bed elevation, bed rest for 2 to 3 days, and stool softeners. Depending on surgeon experience, many ethmoid or sphenoid sinus leaks can be approached endoscopically from below. In other cases, neurosurgical colleagues may approach the skull base defect from above; a pericranial flap can be used to close the defect. Complications can include repeat leakage, infection including meningitis or abscess, enceph alocele, anosmia, postoperative intracranial bleeding, or pneumocephalus. The word epistaxisderives from the Greek epi, meaning on, and stazo, to fall in drops. A nosebleed may present as anterior (bleeding from the nostril), posterior (blood present in the posterior pharynx), or both. It is estimated that $90% of epistaxis cases arise from the anterior nasal septum at Kies selbachs plexus, also known as Littles area. However, the nasal blood supply involves both the internal and external carotid systems and brisk bleeding can arise posteriorly. Major vessels include anterior ethmoid, posterior ethmoid, sphenopalatine, greater palatine, and superior labial arteries. N Epidemiology Most nosebleeds are self-limited, not requiring medical intervention. N Clinical Signs and Symptoms Patients will report bleeding from the nares or the mouth. There may be an obvious antecedent nasal trauma, surgery, or foreign body reported. Differential Diagnosisthe e x i s t e n c e o f e p i s t a x i s i s e s t a b l i s h e d o n h i s t o r y a n d e x a m. A v a r i e t y o f underlying local and systemic conditions should be considered (Table 3. Consider juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma in any teenage male with a unilateral sinonasal mass and epistaxis. Chemotherapy Intranasal illicit drug use Infection Tuberculosis, syphilis, rhinoscleroma, viral Other N Evaluation History In most cases, the approach to the patient begins with a thorough history. The exception to this rule is the patient with severe active bleeding or hemodynamic instability that must first be corrected. Important historical information should include how long nosebleeds have been occurring, their frequency, whether bleeding is typically left or right-sided and anterior or posterior, how long nosebleeds last, and whether packing or cauteriza tion has ever been required. If recent sinonasal surgery has occurred, obtaining operative notes may be helpful. General information that is relevant includes a prior history of easy bruising or bleeding; a family history of such problems or known bleeding disorder; bleeding problems with previous surgeries or dental work; his tory of anemia, malignancy, leukemia, lymphoma, or chemotherapy; other systemic illnesses; or recent trauma. Also consider vitamins such as vitamin E, and other supplements or herbs, many of which can promote bleeding. Rhinology 231 alcohol abuse can be related to coagulation disorders from impaired liver synthetic function as well as malnutrition and vitamin deficiencies; illicit intranasal drug use may be causative. In summary, awareness and treat ment of systemic conditions may be required to obtain definitive effective management of epistaxis. It is essential to have a nasal speculum and headlight, Frazier tip suctions, and oxymeta zoline (Afrin; Schering-Plough Healthcare Products Inc. If topical 4% cocaine is available, this is a very effective decongestant and anesthetic, used sparingly. Often, the otolaryngologist will need to first remove improperly placed or ineffective packing materials. Removal of clots with suction will facilitate identification of bleeding sites, using the equipment described above.