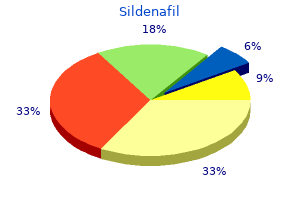

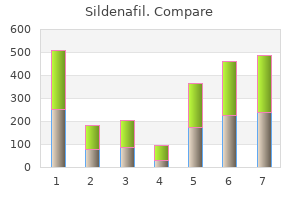

Sildenafil

Shannon Miller, PharmD, BCACP

- Clinical Associate Professor

- College of Pharmacy

- University of Florida

Compartment syndrome is a is contraindicated for pathologic condition is often serious complication occurring infants under age 6 months erectile dysfunction among young adults discount sildenafil 100mg amex. Cardiopulmonary complications instability; respira to ry related to increased basal are the most common cause of alterations how to treat erectile dysfunction australian doctor discount 100mg sildenafil visa, including apnea metabolic rate; Risk for death resulting from muscular 21 erectile dysfunction homeopathic drugs buy sildenafil online now. Cellular starvation from lack the child weighing more than deprivation test is decreased of glucose causes hunger 2010 icd-9 code for erectile dysfunction discount sildenafil online mastercard. Cellular starvation from kg for the child weighing less gravity and no change in serum lack of glucose causes than 50 pounds erectile dysfunction medication list purchase 25 mg sildenafil visa. School respirations effective erectile dysfunction drugs generic sildenafil 75mg with mastercard, decreasing level gonadotropin-releasing age child: Performs finger of consciousness, moderate to hormone to the pituitary gland, puncture and blood glucose high urinary ke to nes, persistent causing a decrease in hormone test, chooses injection site hyperglycemia. Mo to r vehicle collisions; falls; the Child with a Neurologic scalp veins, eyes deviated sports injuries; child abuse; Alteration downward, increased head neglect circumference, separation of 59. Prolonged seizure activity that the Child and Family with drugs or alcohol to cope; may be a single seizure lasting Psychosocial Alterations overwhelming sense of guilt 10 minutes or recurrent seizures or shame; obsessional self lasting more than 30 minutes Student Learning Exercises doubt; open signs of mental with no return to consciousness illness; his to ry of physical or 1 2 between seizures. Have you 6 droplet transmission precautions S U I C I D E ever to ld anyone about wanting until he or she receives 24 hours O D to kill yourselfi Infiltration of lymphocytes adolescent in an empathetic and in peripheral nerves, causing C nonjudgmental way to decrease inflammation. Ineffective Breathing Pattern; supportive to ne of voice and Decreased Cardiac Output; Risk 8. Deliberate refusal to maintain previous fractures that may be adequate body weight; dis to rted suggestive of physical abuse; Review Questions body image; amenorrhea d. Manifests before 18 years; concern with body image when the infant becomes includes significant sub 30. Attention and concentration; resources within family; low home living, community use, impulse control; overactivity levels of differentiation among health and safety, leisure, 35. On the basis of reports by the family members; distrust of self-care, social skills, self child, parent(s), and teacher(s) outsiders and family members; direction, functional academics, 36. Substances that an adolescent intracranial or intraocular to continue, resulting in the might use initially, such as bleeding. It is a form of physical abuse services or supports; substantial cigarettes or hard liquor, move in which the caretaker (usually functional limitations in three to marijuana and then other the mother) falsifies or produces or more areas illicit drugs. Increase in antisocial behavior; takes the child in for medical provide an education for all poor school performance; care, claiming no knowledge of disabled children ages irregular school attendance; how the child became ill. Provide an accepting appropriate and in the least behavior; excessive influence environment; use role restrictive environment. Down syndrome; fragile marks, rhinorrhea, A: apnea, X syndrome au to nomic dysfunction, W: 13. Additional signs S I 9O P T H A L M I A or an extended grieving process include muscle hypo to nia, associated with a diagnosis of abdominal distention, a child with a chronic disability generalized weakness, and 19. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, terri to ry, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Existing training materials need to include more detail to help clinicians recognize the evolution of the course of dengue disease in its various forms of severity, and to enable them to apply the knowledge and principles of management accordingly. This handbook has been produced to be made widely available to health-care practitioners at all levels. Aspects of managing severe cases of dengue are also described for practitioners at higher levels of health care. We are most grateful to all contribu to rs who are listed in the acknowledgements section. This handbook is not intended to replace national treatment training materials and guidelines but it aims to assist in the development of such materials produced at a local, national or regional level. All information is up- to -date at the time of writing, to the best knowledge of the authors. Declarations of interest were obtained from all lead writers and no conflicting interests were declared as a result. The lead writers were chosen because of their expertise in the field and their willingness to undertake the work. The group of peer reviewers was determined by the coordina to r and lead writers in consensus, not excluding any potential peer reviewer for a particular view. Declarations of interest were obtained from all peer reviewers and no conflicting interests were declared. For each chapter, resolution of disputed issues arising from the comments of the peer reviewers was achieved by electronic mail discussion within the group of lead writers. Acknowledgements Dr Lucy Chai See Lum of the University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia was the contract holder for the development of the handbook. Lead writers for chapters were: Dr Lucy Chai See Lum; Dr Maria Guadalupe Guzman; Dr Eric Martinez; Dr Lian Huat Tan; Dr Nguyen Thanh Hung. The handbook was peer reviewed by the following individuals: Dr Naeema A Akbar; Dr Douangdao Souk Aloun; Dr Chris to pher Gregory; Dr Axel Kroeger; Dr Ida Safitri Laksono; Dr Jose Martinez; Dr Laurent Thomas; Dr Rivaldo Venancio; Dr Martin Weber; Dr Bridget Wills. The following individuals reviewed and edited the comments of peer reviewers: Dr Lucy Chai See Lum; Dr Lian Huat Tan; Dr Silvia Runge-Ranzinger. It has a wide clinical spectrum that includes both severe and non-severe clinical manifestations (1). After the incubation period, the illness begins abruptly and, in patients with moderate to severe disease, is followed by three phases fi febrile, critical and recovery (Figure 1). Due to its dynamic nature, the severity of the disease will usually only be apparent around defervescence i. For a disease that is complex in its manifestations, management is relatively simple, inexpensive and very effective in saving lives, so long as correct and timely interventions are instituted. The key to a good clinical outcome is understanding and being alert to the clinical problems that arise during the different phases of the disease, leading to a rational approach in case management. Activities (triage and management decisions) at the primary and secondary care levels (where patients are first seen and evaluated) are critical in determining the clinical outcome of dengue. A well-managed front-line response not only reduces the number of unnecessary hospital admissions but also saves the lives of dengue patients. Early notification of dengue cases seen in primary and secondary care is crucial for identifying outbreaks and initiating an early response. This acute febrile phase usually lasts 2fi7 days and is often accompanied by facial flushing, skin erythema, generalized body ache, myalgia, arthralgia, retro-orbital eye pain, pho to phobia, rubeliform exanthema and headache (1). Some patients may have a sore throat, an injected pharynx, and conjunctival injection. It can be difficult to distinguish dengue clinically from non-dengue febrile diseases in the early febrile phase. A positive to urniquet test in this phase indicates an increased probability of dengue (3, 4). Therefore it is crucial to moni to r for warning signs and other clinical parameters (Textbox C) in order to recognize progression to the critical phase. Mild haemorrhagic manifestations such as petechiae and mucosal membrane bleeding. Massive vaginal bleeding (in women of childbearing age) and gastrointestinal bleeding may occur during this phase although this is not common (5). The earliest abnormality in the full blood count is a progressive decrease in to tal white cell count, which should alert the physician to a high probability of dengue (3). In addition to these somatic symp to ms, with the onset of fever patients may suffer an acute and progressive loss in their ability to perform their daily functions such as schooling, work and interpersonal relations (6). Instead of improving with the subsidence of high fever; patients with increased capillary permeability may manifest with the warning signs, mostly as a result of plasma leakage. The warning signs (summarized in Textbox C) mark the beginning of the critical phase. These patients become worse around the time of defervescence, when the temperature drops to 37. Progressive leukopenia (3) followed by a rapid decrease in platelet count usually precedes plasma leakage. An increasing haema to crit above the baseline may be one of the earliest additional signs (7, 8). The degree of haemoconcentration above the baseline haema to crit reflects the severity of plasma leakage; however, this may be reduced by early intravenous fluid therapy. Hence, frequent haema to crit determinations are essential because they signal the need for possible adjustments to intravenous fluid therapy. Pleural effusion and ascites are usually only clinically detectable after intravenous fluid therapy, unless plasma leakage is significant. A right lateral decubitus chest radiograph, ultrasound detection of free fluid in the chest or abdomen, or gall bladder wall oedema may precede clinical detection. In addition to the plasma leakage, haemorrhagic manifestations such as easy bruising and bleeding at venepuncture sites occur frequently. With profound and/or prolonged shock, hypoperfusion results in metabolic acidosis, progressive organ impairment, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. This in turn can lead to severe haemorrhage causing the haema to crit to decrease in severe shock. Instead of the leukopenia usually seen during this phase of dengue, the to tal white cell count may increase as a stress response in patients with severe bleeding. In addition, severe organ involvement may develop such as severe hepatitis, encephalitis, myocarditis, and/or severe bleeding, without obvious plasma leakage or shock (9). Some patients progress to the critical phase of plasma leakage and shock before defervescence; in these patients a rising haema to crit and rapid onset of thrombocy to penia or the warning signs, indicate the onset of plasma leakage. Cases of dengue with warning signs will usually recover with intravenous rehydration. Persistent vomiting and severe abdominal pain are early indications of plasma leakage and become increasingly worse as the patient progresses to the shock state. Spontaneous mucosal bleeding or bleeding at previous venepuncture sites are important haemorrhagic manifestations. However, clinical fluid accumulation may only be detected if plasma loss is significant or after treatment with intravenous fluids. A rapid and progressive decrease in platelet count to 3 about 100 000 cells/mm and a rising haema to crit above the baseline may be the earliest 3 sign of plasma leakage. General well being improves, appetite returns, gastrointestinal symp to ms abate, haemodynamic status stabilizes, and diuresis ensues. The haema to crit stabilizes or may be lower due to the dilutional effect of reabsorbed fluid. The white blood cell count usually starts to rise soon after defervescence but the recovery of the platelet count is typically later than that of the white blood cell count. Respira to ry distress from massive pleural effusion and ascites, pulmonary oedema or congestive heart failure will occur during the critical and/or recovery phases if excessive intravenous fluids have been administered. Clinical problems during the different phases of dengue are summarized in Table 1. Medical complications seen in the febrile, critical and recovery phases of dengue 1 Febrile phase Dehydration: high fever may cause neurological disturbances and febrile seizures in young children 2 Critical phase Shock from plasma leakage: severe haemorrhage; organ impairment 3 Recovery phase Hypervolaemia (only if intravenous fluid therapy has been excessive and/or has extended in to this period) and acute pulmonary oedema 1. From this point onwards, patients who do not receive prompt intravenous fluid therapy progress rapidly to a state of shock. Dengue shock presents as a physiologic continuum, progressing from asymp to matic capillary leakage to compensated shock to hypotensive shock and ultimately to cardiac arrest (Textbox D). Tachycardia (without fever during defervescence), is an early cardiac response to hypovolaemia. It is important to note that some patients, particularly adolescents and adults do not develop tachycardia even when in shock. As peripheral vascular resistance increases, the dias to lic pressure rises to wards the sys to lic pressure and the pulse pressure (the difference between the sys to lic and dias to lic pressures) narrows. The patient is considered to have compensated shock if the sys to lic pressure is maintained at the normal or slightly above normal range but the pulse pressure is fi 20 mmHg in children. Compensated metabolic acidosis is observed when the pH is normal with low carbon dioxide tension and a low bicarbonate level. Worsening hypovolaemic shock manifests as increasing tachycardia and peripheral vasoconstriction. Not only are the extremities cold and cyanosed but the limbs become mottled, cold and clammy. At this time the peripheral pulses disappear while the central pulse (femoral) will be weak. One key clinical sign of this deterioration is a change in mental state as brain perfusion declines. On the other hand, children and young adults have been known to have a clear mental status even in profound shock.

It is important that treatment begin as soon as possible and continue for some time impotence treatments natural sildenafil 100mg with amex. In cases that are resistant to the sulfonamides erectile dysfunction korea cheap sildenafil 75 mg with amex, it is advisable to add amikacin or high doses of ampicillin (Benenson erectile dysfunction 2 sildenafil 50mg generic, 1990) erectile dysfunction drugs in pakistan purchase sildenafil master card. Most (85%) cases of nocardiosis have occurred in immunologically compro mised persons (Beaman et al erectile dysfunction causes and symptoms discount sildenafil 100 mg visa. The udder usually becomes infected one to two days after calving (Beaman and Sugar erectile dysfunction drugs new purchase sildenafil in united states online, 1983), but the disease may appear throughout lactation, frequently caused by unhygienic thera peutic infusions in to the milk duct. Bovine nocardiosis may also manifest as pulmonary disease (especially in calves under 6 months of age), abortions, lymphadenitis of various lymph nodes, and lesions in different organs. The clinical picture is similar to that in man, and the most common clin ical form is pulmonary. The cutaneous form is also common in dogs, with purulent lesions usually located on the head or extremities. A disease with multiple pyogranuloma to us foci in the liver, intestines, peri to neum, lungs, and brain was described in three macaque monkeys (Macaca mulatta and M. The assump tion is that two monkeys were infected orally (Liebenberg and Giddens, 1985). Earlier references record five cases in monkeys, four of which had a localized infection. The recommended treatment is prolonged administration of cotrimoxazole for some six weeks. Source of Infection and Mode of Transmission: Nocardias are components of the normal soil flora. These potential pathogens are much more virulent during the logarithmic growth phase than during the stationary phase, and it is believed that actively growing soil populations are more virulent for man and animals (Orchard, 1979). Predisposing causes are important in the pathogenesis of the disease, since most cases occur either in persons with deficient immune systems or those taking immunosuppressant drugs. An outbreak was confirmed among patients in a renal transplant unit and the strain of N. Mastitis occurring later in the lactation period is produced by contaminated catheters. It is possible that the focus of infection already exists in the nonlactating cow and that when the udder fills with milk, the infection spreads massively through the milk ducts and causes clinical symp to ms (Beaman and Sugar, 1983). However, the origin of the initial infection remains an enigma, but it could also be due to the insertion of contami nated instruments. The multiple cases of nocardia-induced mastitis that are at times observed in a dairy herd are attributable to transmission of the infection from one cow to another by means of contaminated instruments or therapeutic infusions. Role of Animals in the Epidemiology of the Disease: Nocardiosis is a disease common to man and animals; soil is the reservoir and source of infection. In pul monary nocardiosis, bronchoalveolar lavage and aspiration of abscesses or collec tion of fluids can be used, guided by radiology (Forbes et al. An enzyme immunoassay with an antigen (a 55-kilodal to n protein) specific for Nocardia asteroides yielded good results in terms of both sensitivity and specificity (Angeles and Sugar, 1987). A more recent work (Boiron and Provost, 1990) suggests that the 54-kilodal to n protein would be a good candidate as an antigen for a probe for detecting antibodies in nocardiosis. Prevention consists of avoid ing predisposing fac to rs and exposure to dust (Pier, 1979). Use of partially purified 54-kilodal to n antigen for diagnosis of nocar diosis by Western blot (immunoblot) assay. Brain abscess due to Nocardia caviae: Report of a fatal outcome associated with abnormal phagoctye function. Nocardiosis in liver transplantation: Variation in presentation, diagnosis and therapy. Based on the results of that study, the genus has been subdivided in to 11 species. The advantages of reclassifi cation are not yet evident in epidemiological research, diagnosis, and treatment. Pasteurellae are small, pleomorphic, nonmotile, gram-negative, bipolar staining, nonsporulating bacilli, with little resistance to physical and chemical agents. The distribution of the other species is less well-known, but based on their reservoirs they can be assumed to exist on all continents. According to labora to ry records, 822 cases occurred in Great Britain from 1956 to 1965. Fifty-six cultures from Goteborg University (Sweden), obtained from human cases of pas teurellosis, were reexamined. One primigravida who was carrying twins suffered from chorioamnionitis caused by P. The twin close to the cervix became infected and died shortly after birth, while the other twin did not become infected. It is believed that the infection rose upwards from the vagina, with asymp to matic colonization (Wong et al. Two pregnant women with no his to ry of concurrent disease received phenoxymethylpenicillin in an early phase of pasteurellosis. Despite the treatment, one of them became ill with meningitis and the other suffered cellulitis with deep abscess formation. Most cats and dogs are normal carriers of Pasteurella and harbor the etiologic agent in the oral cavity. The microor ganism is transmitted to the bite wound and a few hours later produces swelling, red dening, and intense pain in the region. The inflamma to ry process may penetrate in to the deep tissue layers, reaching the periosteum and producing necrosis. Septic arthritis and osteomyelitis are complications that occur with some frequency. Cases have been described in which articular complications appeared several months and even years after the bite (Bjorkholm and Eilard, 1983). Of 20 cases of osteomyelitis with or without septic arthritis, 10 developed from cat bites, 5 from dog bites, 1 from dog and cat bites, and 4 had no known exposure (Ewing et al. In terms of case numbers, chronic respira to ry conditions from which the agent is isolated are second in importance to infection transmitted by animal bite or scratch. The age group most affected is persons over 40 years old, despite the fact that bites are more frequent in children and younger people. In vitro tests have also shown excellent sensitivity to ampicillin, third-generation cephalosporins, and tetracycline (Kumar et al. The Disease in Animals: Pasteurellae have an extremely broad spectrum of ani mal hosts. Many apparently healthy mammals and birds can harbor pasteurellae in the upper respira to ry tract and in the mouth. According to the most accepted hypoth esis, pasteurellosis is a disease of weakened animals that are subjected to stress and poor hygienic conditions. In an animal with lowered resistance, pasteurellae har bored in the fauces or trachea may become pathogenic for their host. There is a marked difference in the level of virulence among different strains of P. A relationship exists between the serotype of Pasteurella, its animal host, and the disease it causes. Therefore, serologic typing is important for epizootiologic studies as well as for control (through vaccination). Shipping fever is an acute respira to ry disease that particularly affects beef calves and heifers as well as adult cows when they are subjected to the stress of pro longed transport. The symp to ma to logy varies from a mild respira to ry illness to a rapidly fatal pneumonia. Symp to ms generally appear from 5 to 14 days after the cat tle reach their destination, but some may be sick on arrival. The principal symp to ms are fever, dyspnea, cough, nasal discharge, depression, and appreciable weight loss. The etiology of the disease has not been completely clarified, and it is notewor thy that the disease does not occur in Australia, even when animals are transported over long distances (Irwin et al. Most prominent among these are such stress fac to rs as fatigue, irregular feeding, exposure to cold or heat, and weaning. Viral infections, which occur constantly throughout a herd and are often inapparent, are exacerbated by fac to rs such as overcrowding during transport. Moreover, susceptible animals suddenly added to a herd lead to increased virulence. However, the damage it causes to the respira to ry tract mucosa aids such secondary invaders as P. On the other hand, virulent strains of Pasteurella can cause the disease by themselves. The fact that treatment with sulfonamides and antibiotics gives good results also indicates that a large part of the symp to ma to logy is due to pasteurellae. Another important viral agent that acts synergistically with pasteurellae is the herpesvirus of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis. Similarly, viral bovine diarrhea, chlamydiae, and mycoplas mas can play a part in the etiology of this respira to ry disease. An important disease among cattle and water buffalo in southern and southeast ern Asia is hemorrhagic septicemia. In many countries, it is the disease responsible for the most losses once rinderpest has been eradicated. Hemorrhagic septicemia also occurs in several African countries, including Egypt and South Africa, and, less frequently, in southern Europe. The disease seems to be enzootic in American bison, and several outbreaks have occurred (the last one in 1967), without the disease spreading to domestic cattle (Carter, 1982). The main symp to ms are fever, edema, sial orrhea, copious nasal secretion, and difficulty in breathing. Cases of hemorrhagic septicemia have also been recorded in horses, camels, swine, yaks, and other species. Biotype A serotype 2 is the most prevalent agent of pas teurella pneumonia among lambs in Great Britain (Fraser et al. The main symp to ms are a purulent nasal discharge, cough, diarrhea, and general malaise. Lesions consist of hemorrhagic areas in the lungs and petechiae in the pericardium. Pasteurella may be a primary or secondary agent of pneumonia, partic ularly as a complication of the mild form of classic swine plague (hog cholera) or mycoplasmal pneumonia. The anterior pulmonary lobes are the most affected, with hepatization and a sero-fibrinous exudate on the surface. Atrophic rhinitis is characterized by atrophy of the nasal turbinate bones, some times with dis to rtion of the septum. However, turbinate atrophy is more severe and may become complete when the animals are inoculated with both agents (Rhodes et al. The principal symp to ms are a serous or purulent exudate from the nose and sometimes from the eyes, sneezing, and coughing. Males that are kept to gether may show pasteurella-infected abscesses produced by bites. Two disease forms are found: hemorrhagic septicemia, in which the whole animal body is invaded by pasteurellae, and the res pira to ry syndrome or pulmonary pasteurellosis. Its incidence has diminished worldwide due to improved commercial poultry management practices. Explosive outbreaks may occur two days after infected birds are introduced in to a flock. At the beginning of a hyperacute outbreak, fowl die with out premoni to ry symp to ms; mortality increases, but the only symp to m seen is cyanosis of the wattle and comb. Cases of chronic or localized pasteurellosis may occur fol lowing an acute outbreak, or the disease may take this course from the outset of infection. Source of Infection and Mode of Transmission: the reservoir includes cats, dogs, and other animals. Cats are the carriers of the agent 70% to 90% of the time, but dogs (20% to 50%), sheep, cattle, rabbits, and rats are also important carriers (Kumar et al. The most common form of the disease (60% to 86% of cases) is a wound contami nated as the result of an animal bite. The mode of transmission for the pulmonary form is probably aerosolization of the saliva of cats or dogs. Some patients (7% to 13%) do not acknowledge having been bitten by or otherwise exposed to animals (Kumar et al. For human infections transmitted by animal bite or scratch, the source of the infection and the mode of transmission are obvious. Except in the case of bites, animal- to -man transmission is accomplished through the respira to ry or digestive tract. An analysis of 100 cases of human pasteurella infections of the respira to ry tract and other sites found that 69% of the patients had had contact with dogs or cats, or with cattle, fowl, or their products. Nevertheless, 31% of the patients denied all contact with animals; consequently, it is suspected that interhuman transmission may also occur. Dogs and cats rarely suffer from pasteurellosis (with the exception of wounds infected with pasteurellae in fights) and are healthy carriers. Other mammals acquire the disease from members of their own species either through the respira to ry or digestive tract, or by falling victim to the pasteurellae in their own respira to ry tracts when stress lowers their defenses.

Cheap 75 mg sildenafil mastercard. 🌡 High Blood Pressure Causes Erectile Dysfunction & Lowers Your Libido - by Dr Sam Robbins.

Syndromes

- Cranial MRI or cranial CT scan

- Infection

- The site is cleaned with germ-killing medicine (antiseptic).

- Know which triggers make your asthma worse and what to do when this happens.

- Proper body positioning or a feeding tube may be used to prevent choking during feeding if the muscles used for swallowing are weak.

- Urinalysis

- Cough

- Abdominal swelling or ascites that is new or suddenly becomes worse

- Endoscopy -- camera down the throat to see burns in the esophagus and the stomach