Liv 52

Virginia Fleming, PharmD, BCPS

- Clinical Assistant Professor, Clinical and Administrative Pharmacy

- University of Georgia College of Pharmacy, Athens, Georgia

https://rx.uga.edu/faculty-member/virginia-fleming-pharm-d/

Examples include maintaining a consistent sleep schedule and planning to take short naps during the day medicine reactions cheap liv 52 100ml online. Otherwise medicine allergies cheap liv 52 online, treatment for narcolepsy typically involves a combination of medications symptoms in children buy generic liv 52 on line. It tends to take about six weeks to nine weeks before it consistently reduces sleepiness symptoms 7 dpo bfp discount liv 52 200ml without prescription. Other antidepressants (atomoxetine treatment 5th toe fracture order liv 52 200 ml with mastercard, clomipramine medications not covered by medicare purchase genuine liv 52 line, fluoxetine, venlafaxine, zimeldine) have been effective and have produced fewer side effects. List of Abbreviations Such changes present a fundamental challenge for any classification of dis General Bibliography. Such developments call for an in-depth revision of the classifi Clinical Field Trials. On the other hand, frequent, major changes in a classification of disorders can be disruptive for both clinical and research practice. At this point, the sleep disorders field has not conducted the type of rigorous re-examination needed to support a substantive revision of its diagnostic classifi cation. The listing of disorders has been made accessible by printing it on the inside cover of the book. Text for individual disorders has been revised to clarify textual errors, standardize format across disorders, and correct minor factual errors. Changes were made only if the fundamental accuracy of the original text was in question. Sleep specialists and interested parties from around the Academy of Sleep Medicine. National and international sistent with other diagnostic classifications such as the Diagnostic and meetings have been held to openly discuss the ongoing developments. This man Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition (American Psychiatric Association) ual will lead to more-accurate diagnoses of the sleep disorders, improved treat and the International Classification of Diseases (World Health ment, and stimulation of epidemiologic and clinical research for many years. These committee members generously any confusion stemming from the minor textual changes and change in and selflessly gave of their time to accumulate the material for this volume. Many other contributors, most of whom are included in the list of con (Emmanuel Mignot, M. I would like to thank my wife Marie-Louise, not only for her support and encouragement throughout the long process of developing the manual, but also for her typing and editorial assistance. Careful and accurate secretarial assistance was also provided by Sonia Colon and Elaine Ullman. The coding system is not presented for third-party-payer reimbursement purposes or to be regarded as meeting the requirements for state or federal healthcare agencies, such as those of the Minnesota Health Care Financing Administration. For such purposes, it is recommended that local and federal guide lines should be consulted and used whenever appropriate. Disorders and Research Center, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas Frank Zorick, M. Unit, and Director of Research, Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Charles F. Southwestern Medical Center; Consulting Director, Sleep/Wake Disorders Co-Chair Vincent Zarcone, M. Advisory committees were established in order to develop the text of the indi Wolfgang Schmidt-Nowara, M. The groups were organized Primary Snoring along traditional systematic lines for ease of developing the texts. The groupings Central Alveolar Hypoventilation Sleep-related Asthma were not intended to convey the impression that the classification committee Syndrome Sleep Choking Syndrome believes that any particular disorder solely pertains to one system. The groups Sleep-related Abnormal Swallowing Sleep-related Laryngospasm could easily have been organized differently, but the groupings shown here were Syndrome Congenital Central Hypoventilation regarded as being preferable for the purposes of developing this manual. Most of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Syndrome the subcommittee members had the opportunity to view and comment on each Disease Sudden Infant Death Syndrome disorder draft in their section. Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome Infant Sleep Apnea Central Sleep Apnea Syndrome Altitude Insomnia x xi Neurologic Disorders Other Sleep-related Medical Disorders Christian Guilleminault, M. Draft material for this manual was periodically forwarded to the following Timothy Monk, Ph. Many of the interna tional advisers contributed drafts of individual disorders, communicated with Short Sleeper Delayed Sleep-Phase Syndrome their regional societies about the classification, or held a forum for discussion of Shift-Work Sleep Disorder Non-24-Hour Sleep-Wake the classification text material. Advanced Sleep-Phase Syndrome Syndrome Irregular Sleep-Wake Pattern Time-Zone Change (Jet-Lag) Michel Billiard, M. This introduction describes the rationale behind the major changes that have Bernard Burack, M. The group decided to survey sleep specialists to determine the Christian Guilleminault, M. The response was excellent: 160 fully completed questionnaires were received Andre Kahn, M. The four sections of the original classification provided a useful structure for Stuart J. However, mentalize the sleep disorders in a manner that would inhibit a multidisciplinary disorders listed within the third section, the disorders of the sleep-wake schedule approach to diagnosis. Classifying the disorders by pathophysio mary complaint of insomnia or excessive sleepiness. The dyssomnias are further logic mechanism was preferred, and to have divided the schedule disorders by pri subdivided, in part along pathophysiologic lines, into the intrinsic, extrinsic, and mary complaint would have been less acceptable. The distinction into intrinsic and extrinsic sleep somnia listing was long and did not have subcategory organization. Nathaniel Kleitman ini mended that the information contained in the text of the individual disorder be tially proposed this grouping of the sleep disorders in his extensive monologue on substantially improved. The few unsatisfactory entries resulted from the text being sleep disorders that was published in 1939. The survey also demonstrated that clinicians required more diagnostic infor the primary sleep disorders (dyssomnias and parasomnias) are separated from mation about respiratory and neurologic disorders, so these sections were expand the medical or psychiatric sleep disorder section. With advances in understanding the pathophysiologic bases of the tion was considered, but this separation may have produced an artificial distinc sleep disorders, the primary sleep disorders may be organized along pathologi tion between the same disorder in different age groups. The sleep disorders were arbi the questionnaire survey assessed the potential utility of an axial system for trarily grouped into seven sections for ease in accumulating the text. The members of the system would be helpful for treatment planning and the prediction of outcome. A seven committees, listed at the beginning of this book, were selected for their two or three-axes system was preferred. This group included members repre senting the European Sleep Research Society, the Japanese Society of Sleep Based upon the information obtained from the questionnaire survey, several Research, and the Latin American Sleep Society. In addition to the subcommittees different classification systems were reviewed, and additional proposals were and international advisers, many other sleep specialists offered suggestions on the solicited. A classification for statistical and epidemiologic purposes required that organization of the classification and assisted in reviewing and developing text each disorder be listed only once. The classification committee developed the diagnoses and diagnostic codes in Because the pathology is unknown for most sleep disorders, however, the classi a manner compatible with the North American version of the International fication was organized in part on physiologic features, i. Sleep disorders coded in sections other than the second section, the parasomnias, comprises disorders that intrude into or #307. This section was developed in recognition of the new and rapid advances in sleep disorders medi cine. The classification provides a unique code number for each sleep disorder so that dis 2. Axis B orders can be efficiently tabulated for diagnostic, statistical, and research purpos Axis B lists tests and procedures that are performed in the practice of sleep dis es. Other medical tests that commonly may be rec whereby clinicians can standardize the presentation of relevant information ommended for patients who have sleep disorders also are listed in axis B. Because knowledge the axial system assists in reporting appropriate diagnostic information, either of the objective features of many sleep disorders is still in its infancy, the axis B in the clinical summaries or for database purposes. These diagnoses are stat graphic and other forms of testing can be stated and coded for statistical and data ed according to the recommendations in the text material of this volume. A standardized means of documenting this information will assist ond axis, axis B, contains the names of the procedures performed, such as in allowing future research to determine which sleep abnormalities have particu polysomnography, or the names of particular abnormalities present on diagnostic lar diagnostic significance. Any medical or psychiatric dis the main symptom, and the severity or duration of the disorder. Age of Onset the text of each disorder has been developed in a standardized manner to this section includes the age range within which the clinical features first ensure the comprehensiveness of descriptions and consistency among sections. Synonyms and Key Words this section includes the relative frequency with which the disorder is diag nosed in each sex. This section includes terms and phrases that have been used or are currently used to describe the disorder. The presence of a disor overall diagnostic group heading or code number may be excluded from the text der in several family members, however, does not necessarily mean that the dis description and, therefore, may have a separate text; such disorders are indicated order has a genetic basis. When appropriate, an explanation is given for the choice of the preferred name of the disorder. Essential Features this section describes, if known, the gross or microscopic pathologic features of the disorder. When the exact pathologic basis of the sleep disorder is not this section includes one or two paragraphs that describe the predominant known, the pathology of the underlying medical disorder is presented. Associated Features this section includes other disorders or events that may develop during the this section contains those features that are often but not invariably present. Separating complications from the associated features may also includes complications that may be a direct consequence of the disorder. Polysomnographic Features this section describes the usual clinical course and outcome of the untreated disorder. This section presents the characteristic polysomnographic features of the dis order, including the best diagnostic polysomnographic measures. Predisposing Factors may be presented on the number of nights of polysomnographic recording required for diagnosis and whether certain special conditions are necessary for this section describes internal as well as external factors that increase the appropriate interpretation of the polysomnographic results. Other Laboratory Features this section presents the prevalence of the specific sleep disorder, if the preva this section describes features of laboratory tests, other than polysomnograph lence is known. The prevalence is the proportion of individuals who at some time ic procedures, that aid in either establishing the diagnosis or eliminating other dis have a disorder. For some disorders, the exact prevalence is unknown, and only orders that may have a similar presentation. Such tests may include blood tests, the prevalence of the underlying medical disorder can be stated. Differential Diagnosis according to specific information given in the text of each disorder. For example, the this section includes disorders that have similar symptoms or features and that patient with a disorder of acute duration may be examined and treated differently should be distinguished from the disorder under discussion. As with the diag nostic and severity criteria, future research will refine the duration criteria. Diagnostic criteria were considered by the classification committee cardinal clinical and diagnostic features of the disorder. Classic articles from a to be helpful not only for clinical but also for research purposes. Criteria are pre variety of authors and sources have been selected, and the number of abstracts and sented that allow for the unequivocal diagnosis of a particular disorder. The final assignment of a particular diagnosis depends upon clinical judgment, and the criteria do not exclude those disorders in which there may be F. In order to allow greater specificity for tests used in the stantiate an otherwise unclear diagnosis. These criteria should provoke discussion practice of sleep disorders medicine, an expanded code number is used. Minimal Criteria ically to code symptoms, the severity and duration criteria, and the features seen the minimal criteria aid in the early diagnosis of a sleep disorder, usually during polysomnographic testing. The main diagnostic criteria assist in making a final diagnosis; however, all the information required may not be available, and appro 1. Axis B: Procedure Feature Codes priate diagnostic testing, such as polysomnography, may not be widely accessible. Therefore, the minimal criteria are mainly for general clinical practice or for mak Listed here are the normal and abnormal procedure features seen during ing a provisional diagnosis. The minimal criteria usually are dependent upon the available patient history and clinical features. To facilitate record keeping of the sleep disorders encountered, a database sys 17. The purpose of this database is to establish a format for epi demiologic tracking of sleep disorders at sleep disorders centers. Differential-Diagnosis Listing cal value for differentiating severity levels was avoided. A differential-diagnostic listing of the three main presenting sleep complaints is insomnia, excessive sleepiness, and sympto 18. These symptoms are used as subheadings, and the disorders are organized in a uniform manner in each sec Duration criteria allow the clinician to categorize how long a particular disor tion.

It is most often demonstrated in excited schizophrenic states medications 4 less cheap liv 52 120ml with amex, with mental retardation and with organic states such as dementia treatment renal cell carcinoma generic liv 52 200ml line, especially if dysphasia is also present medications just like thorazine purchase liv 52 with a mastercard. Excited patients with schizophrenia may also speak loudly; intonation and stresses on words may be idiosyncratic and inappropriate medicine etymology purchase liv 52 120ml amex. The speed and fow of talk mirrors that of thought and has been dealt with in Chapter 9 symptoms xanax addiction cheap liv 52 120ml fast delivery. In mania symptoms nausea purchase liv 52 mastercard, the speed of association may be so rapid as to disrupt sentence structure completely and render it meaningless, while in depression retardation may so inhibit speech that only unintelligible syllables, often of a moaning nature, are produced. Organic Disorders of Language Dysphasic symptoms are probably more useful clinically than any other cognitive defect in indi cating the approximate site of brain pathology (David et al, 2007). However, the auditory, visual and motor mechanisms of speech are spread through several different parts of the brain; often, several functions are affected and lesions are usually diffuse, and thus precise brain localization is not often possible. Ninety per cent of right-handed people without any brain damage have speech located in the left hemisphere, and 10 per cent have right hemisphere speech. Among those who are left-handed or ambidextrous, 64 per cent have left hemisphere speech, 20 per cent right hemisphere and 16 per cent bilateral speech representation. However, aphasia implies the loss of language altogether, and dysphasia impairment of, or diffculty with, language. Dysphasia is conventionally divided for classifcation purposes into sensory (receptive) and motor (expressive) types. Very frequently, there is a global impairment of language with evidence of impairment of both elements. Pure Word Deafness (Subcortical Auditory Dysphasia) In pure word deafness, the patient can speak, read and write fuently, correctly and with compre hension. He cannot understand speech, even though hearing is unimpaired for other sounds; he hears words as sounds but cannot recognize the meaning even though he knows that they are words. Pure Word Blindness (Subcortical Visual Aphasia) the patient with pure word blindness can speak normally and understand the spoken word; he can write spontaneously and to dictation but cannot read with understanding (alexia). Such a patient will also suffer a right homonymous hemianopia (loss of the right half of the feld of vision in both eyes) and an inability to name colours even though they can be perceived. Primary Sensory Dysphasia (Receptive Dysphasia) Patients with primary sensory dysphasia are unable to understand spoken speech, with loss of comprehension of the meaning of words and of the signifcance of grammar. Speech is fuent, with no appreciation of the many errors in the use of words, syntax and grammar. Conduction dysphasia could be considered to be a type of sensory dysphasia in which sensory reception of speech and writing are impaired, in that the patient cannot repeat the message although he can speak and write. Speech is fat, the structure of sentences generally correct and understanding unimpaired. Jargon Dysphasia In jargon dysphasia speech is fuent, but there is such gross disturbance to words and syntax that it is unintelligible. There is no local disturbance of muscles required in speaking, and the disability is an apraxia limited to movements required for speech. Pure Agraphia Pure agraphia is an isolated inability to write which may also occur with unimpaired speech (agraphia without alexia); there is normal understanding of written and spoken material. Primary Motor Dysphasia In primary motor dysphasia there is disturbance to the processes of selecting words, constructing sentences and expressing them. Speech and writing are both affected, and there is diffculty in carrying out complex instructions, even though understanding for both speech and writing may be preserved. The patient fnds it diffcult to choose and pronounce words, and speech is hesitant and slow; he recognizes his errors, tries to correct them and is clearly upset. Speech is attempted and recognized as spoken words, but words are omitted, sentences shortened and perseveration occurs. In alexia with agraphia, the patient is unable to read or write, but speak ing and understanding speech are preserved. Alexia in this condition is similar to that of pure word blindness: the patient cannot understand words that are spelt out aloud, showing that he is effectively illiterate because of disturbance of the visual symbolism of language. Two types, expressive and receptive, are described: transcortical motor dysphasia and transcortical sensory dysphasia. This description has been exclusively concerned with the symptoms; precise description of the ana tomical lesions and of associated neurological symptoms is outside our scope. It is important to distinguish the phenomena of dysphasia, perhaps with neologisms and defects of syntax, from the word salad of schizophrenia with superfcially similar defects of language. Verbigeration describes the repetition of words or syllables that expressive aphasic patients may use while desperately searching for the correct word. All the major categories of psychiatric disorder may manifest mutism: learning disability, organic brain disease (sometimes drug-related), functional psychosis and neurosis and personality disorder. Some more specifc causes include depressive illness, cata tonic schizophrenia and dissociative disorder. Mutism occurs as an essential element of stupor (Chapter 3), and it is necessary to assess the level of consciousness as part of a full neurological examination for all patients with this sign. If there is no lowering of consciousness, as in functional psychoses and neuroses, it is likely that the mute patient understands everything that is said around him. As well as specifc brain disorders, the causes of stupor include general metabolic disorders that also affect the brain, such as hepatic failure, uraemia, hypothyroidism and hypoglycaemia. Schizophrenic Language Disorder Defective communication in language is the defning characteristic of schizophrenia according to Crow (1997), and it is associated with genetic variation at the time language was acquired by Homo sapiens. The use of language by people with schizophrenia can differ from that in normal people, and this difference can be subtle and unrelated to positive symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations. There is good reason to believe that the abnormalities of language use are associated with thought disorder. The precise nature of the language abnormality has so far defed clarifcation, and this account is provisional; it describes the way some of the phenomena have been viewed and conceptualized. There is no single explanatory theory that unifes the disparate abnormalities that have been observed and described. Investigation into language disorder may be ascribed to one of the four models shown in Table 10. Thought disorder may be revealed in the fow of talk (as in Chapter 9), disturbed content and use of words and grammar, and in the inability to conceptualize appropriately. Some of the ways in which clinicians have categorized schizo phrenic thought disorder manifesting in speech are linked in Table 10. Kraepelin (1919) defned akataphasia as a disorder in the expression of thought in speech. Loss of the continuity of associations, which implied incompleteness in the development of ideas, was the frst of the functions included among the fundamental symptoms of schizophrenia by Bleuler (1911). Cameron (1944), in describing asyndesis, considered there to be an inability to preserve conceptual boundaries and a marked paucity of genuinely causal links. When the thematic organization of speech was analyzed for patients with positive speech disorder (incoherence of speech) or negative speech disorder (poverty of speech), there was no difference found: speech-disordered patients, positive as well as negative, showed cognitive restriction and produced fewer inferences than non-speech disordered patients. A defciency in the logic of deductive reasoning in schizophrenia was suggested by Von Domarus (1944). Some of the abnormalities of thinking expressed in speech observed by Schneider have been discussed in Chapter 9. Some types of thought disorder, such as neologism and blocking, occurred too infrequently to have diagnostic signifcance. However, she found high reliability between raters with many types of thought disorder and also discrimination between different psychotic illnesses. Derailment, loss of goal, poverty of content of speech, tangentiality and illogicality were particularly characteristic of schizophrenia. Derailment implies loosening of association so that ideas slip on to either an obliquely related, or totally unrelated, theme. Loss of goal is the failure to follow a chain of thought through to its natural conclusion. Tangentiality means replying to a question in an oblique or even irrelevant manner. Illogicality implies drawing conclusions from a premise by inference that cannot be seen as logical. Misuse of Words and Phrases the patient with schizophrenia sometimes shows misuse of words in that he has, in the terminol ogy of Kleist (1914), a defect of word storage. He has a restricted vocabulary and so uses words idiosyncratically to cover a greater range of meaning than they usually encompass. These are called stock words or phrases, and their use will sometimes become obvious in a longer conversation in which an unusual word or expression may be used several times. This abnormality appears partly to refect a poverty of words and syntax and also an active tendency for words or syllables by association to intrude into thoughts, and therefore speech, soon after utterance. They also appear to be stock words or phrases in that they are used with greater frequency and with a greater range of meaning than is normal and correct. Words carry a semantic halo, that is, their constellation of associations is greater than just the dictionary meaning of the word. The constellations of associations in patients are disordered in that they often make apparently irrelevant associations. These may be explained by misperception of auditory stimuli with specifc inattention; the actual mediation of associations in patients with schizophrenia may be similar to that in healthy people. This comes some way to explaining why the associations seem appropriate subjectively to the patient himself, as he does not realize that he has misper ceived the cue: it seems reasonable to him but is quite irrelevant to the interviewer. Although such a word does actually exist, the patient had no notion of this nor what it meant. He created the word to describe a unique experience of his for which no adequate word existed. There is a marked tendency in schizophrenia to show intrusion of the domi nant meaning when the context demands the use of a less common meaning. An analysis of responses shows that dominant meanings, here a court of law, intrude into the responses quite frequently, but intrusion of minor meanings is less frequent. This is unlike the clang associations that occur nor mally in poetry and in humour and also in manic speech, in which the clang occurs in terminal syllables. The repetitiveness of speech disorder is also thought to be associated with the intrusion of associations: the normal process of eliminating irrelevant associations does not take place, so that a word in a clause will provoke associations by pun, clang and ideational similarity. When that clause is completed, a syntactically correct clause may then be inserted, disrupting meaning but demonstrably associated with that previous word or idea. Maher considers that an inability to maintain attention may account for the language distur bances seen in some patients. Disturbed attention allows irrelevant associations to intrude into speech, similarly to the disturbance affecting the fltering of sensory input. In this theory, normal coherent speech is seen as the progressive and instantaneous inhibition of irrelevant associations to each utterance, and so the determining tendency proceeds with the active elimination of those associations that are not goal-directed.

Discount liv 52 100 ml without prescription. How To Get Your ENERGY Back FAST After Opiate Withdrawal.

However symptoms when pregnant buy generic liv 52 60ml on line, fantasy thinking may also reveal itself in the denial of external events treatment diverticulitis buy liv 52 200 ml on-line. The observations for which the psychodynamic explanation of ego defence mechanisms have been described are relevant in this context symptoms ectopic pregnancy liv 52 200ml. Fantasy thinking denies unpleasant reality treatment thesaurus buy liv 52 60 ml without prescription, even though the fantasy itself may also be unpleasant medications descriptions liv 52 100ml overnight delivery. This rearranging or transformation of reality is shown by neurotic patients habitually and all people occasionally treatment episode data set purchase 100 ml liv 52 visa. There are at least three components of imagination: mental imagery, counterfactual thinking and symbolic repre sentation. Mental imagery refers to the ability to create image-based mental representations of the world. Counterfactual thinking refers to the capacity to disengage from reality in order to think of events and experiences that have not occurred and may never occur. Symbolic representa tion is the use of concepts or images to represent real world objects or entities (Roth, 2004). A facet of this type of thinking that comes from a psychoanalytic theoretical stance is the concept of maternal reverie (Bion, 1962). Bion would regard this as a necessary factor in the healthy development of the self-sensation of the baby; when maternal reverie breaks down, for example in puerperal depression, the baby experi ences this as distress. Problem solving is defned as the set of cognitive processes that we apply to reach a goal when we must overcome obstacles to reach that goal, and reasoning is the cognitive process that we use to make inferences from knowledge and to draw conclusions. These aspects of thinking are distinct but related, so that reasoning can be involved in problem solving (Smith and Kosslyn, 2007). Strategies for problems involve the use of heuristics, that is, rules of thumb that usually give the correct answer. Analogic reasoning involves the application of solutions to already known problems to new problems with similar characteristics. For example, if you lose the keys to your locked briefcase, you can apply the knowledge to this new problem that sharp-ended implements can be used to open padlocks. Inductive reasoning depends on the use of specifc known instances to draw an inference about unknown instances. Commonly, this is formulated as generalizing from a single instance to all instances or from some members of a category known to have a given property to other instances of that category. Deductive reasoning involves an argument in which if the premises are true, the conclusion cannot be false. This is usually studied by way of syllogism: (a) all Martians are green, (b) my father is a Martian, (c) my father is green. This is the capacity for abstraction, the ability to theorize about the world, and it includes the categorization of objects or events in the world and the clarifcation of the concepts that determine the category or class under investigation. The sequence of thoughts, with the associa tions linking them, forms the framework of this model, which is represented diagrammatically in Figure 9. There are an enormous number of possible associations, but thinking usually proceeds in a defnite direction for various immediate and compelling reasons. This consistent fow of thinking towards its goal is ascribed to the determining tendency (Jaspers). The idea of associations is not intended to imply that one psychological event evokes another by an automatic, unintelligent, non-verbal refex, but that the thought, which may be expressed verbally or not, is a concept that results in the formation of a number of other concepts, one of which is given prominence by operation of the determining tendency. This model is conjectural but has some value in allowing description of the abnormalities of thinking and speech that occur in mental illness. To develop the metaphor, thoughts are capable of acceleration and slowing, of eddies and calms, of precipitous falls, of increased volume of fow, of blockages. This analogy should not be taken too far, as it is without neurophysiological basis, but it is useful for examining certain abnormalities and is based on subjective experience. In this, there is a logical connection between each of two sequential ideas expressed. It is continuously changing because of the effect of frivolous affect and a very high degree of distractibility. The speed of forming such associations, and therefore of the pattern of thought, is grossly accelerated. Markedly different from the manic fight of ideas with pressure of speech and multiple but linked associations is the confusion psychosis described by Fish (1962). In this, thinking is disor dered while mood and psychomotor activity are unimpaired. In the excited form of this, incoher ent pressure of speech is prominent, the context of which is out of keeping with the situation. There may be transient, almost playful, misidentifcations of people; feeting ideas of reference; and auditory hallucinations. In the inhibited state of confusion psychosis, there is poverty of speech, almost mutism. This is usually a cycloid psychosis in its presentation, and other features of manic-depressive psychosis may be present. The patient is likely to show little initiative and to begin neither planning nor spontaneous activity. When asked a question, he will ponder over it, but as no thought comes to him he makes no response. He has diffculty in making decisions and in concentration; there is loss of clarity of thought and poor registration of those events he needs to remember. In terms of the model of the fow of thinking, in retarda tion there is a poverty in the formation of associations; see Figure 9. Depression, although usually associated with retardation of thought, may occur with agitation; there may be a complex situation with impaired concentration from retardation and a subjective experience of restless, anxious thoughts. Thus, Sutherland (1976), a middle-aged psychologist describing his own mental illness, said, I contemplated throwing myself off the cross-Channel ferry We arrived in Naples and my friends were upset by my condition while feeling powerless to help whilst the others sat at the table I rolled around moaning in the dust. I revisited many of the places I had once loved: the Museo Nazionale with its magnifcent mosaics pillaged from Pompeii, Pompeii itself and Capri. I could not guide the children round Pompeii, since I could not concentrate suffciently to follow the plan. In circumstantial thinking, the slow stream of thought is not impeded by affect but by a defect of intellectual grasp, a failure of differentiation of the fgure from ground. Characteristically, this occurs in patients with epilepsy, and it is seen in other organic states and in mental retardation. On being asked a question, circumstantial thought is shown by the patient in a reply that contains a great welter of unnecessary detail, obscuring and impeding the answer to the question. All sorts of unnecessary associations are explored exhaustively before the person returns to the point. He even has to explain and apologize for these digressions before he can get back to moving towards the goal. However, the determining tendency remains, and he does eventually answer the question. These processes (and others) occur together to give the patient a feeling of confusion and bewilderment. He is likely to complain of feeling bemused, to be lacking in concentration and to be slightly appre hensive of he knows not what. He cannot precisely describe his altered thinking and consequent changes in speech. With derailment, the subject is unable to link the ideas and describes a change in his direction of thinking. With fusion, there is some preservation of the normal chain of associations, but there is a bringing together of heterogeneous elements. These form links that cannot be seen as a logical progression from their constituent origins towards the goal of thought. Two men are controlling the brain through telethapy [sic] or by means of ways of the spirit who open and closes the back channels of my brain releasing words and holding back the truth, by no means will I speak but will answer only to written questions by means of writing, knowing full well the channels of my brain is fltering and only half of what is the truth, also I knowing I am being read not only by a few but many very clever people but not at all acceptable they make people believe that I am some kind of miracle which I am not, I only hold the name Holyland which came to me by marrying Alfred Holyland, only by doing this do they wish to make some false stories of me coming from some special place which I have not. It is dif fcult to represent this diagrammatically, and I hope the result in Figure 9. Thought Blocking Snapping off is the experience a patient with schizophrenia has of his chain of thought, quite unexpectedly and unintentionally, breaking off or ceasing. It is not caused by distraction by other thoughts and, on introspecting, the patient can give no adequate explanation for it; it simply occurs. The patient describes his thoughts as being pas sively concentrated and compressed in his head. It becomes a headlong chase or dance of thoughts and has some of the characteristics of fight of ideas, but it also shows a schizophrenic quality of passivity, being controlled from outside. Perseveration (Chapter 5) is mentioned here as a disturbance of the fow of thinking. The patient retains a constellation of ideas long after they have ceased to be appropriate. An idea from that constellation which occurred in a previous sequence of thought is given in answer to a different question. Disturbance of Judgement A judgement is a thought that expresses a view of reality. To assess whether it is disturbed or not, one needs to measure it against objective fact. This can be diffcult, perhaps requiring consulta tion with an expert in the same feld as the patient. But the opinion that his judgement was disturbed would be confrmed if he had suddenly become convinced about his royalty when a psychiatric nurse had commented to him about the tattoos on his arm, or if he were also found to be hoarding pebbles and dead spiders in an old tobacco tin. Various forms of thought disorder and intellectual defcit may also result in disturbance of judgement. It occurs in clear consciousness with no signs of organic disturbance of the brain. Judgement in other areas of life apart from the delusion can be preserved, and the very ingenious ness the patient uses to explain and defend his delusional belief demonstrates that his essential capacity to think logically is largely intact; only the falsely held belief, the false premise for subse quent beliefs appears disordered. For instance, not all those with delusions of persecution have any frsthand experience of being perse cuted. It is an assumption about the world the patient inhabits, which he does not create by a process of logical conscious thought but from false premises. The mechanism underpinning the often spontaneous development of this false premise is yet to be understood. We can understand why the belief should be within that particular context (associated with his mother; related to interplanetary travel), but we cannot explain how the form of a primary delusion should have occurred.

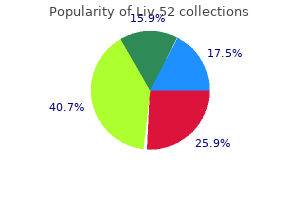

Further treatment for pink eye buy generic liv 52 from india, only 54 doctorates were awarded with a focus on somnology or sleep medicine medications with gluten liv 52 120ml. This workforce is insufficient symptoms 11 dpo liv 52 60 ml free shipping, given the burden of sleep loss and sleep disorders medications like zovirax and valtrex order 120 ml liv 52. Since 1997 treatment ulcer cheap 200ml liv 52 amex, there have been no new requests for application or program announcements for sleep-related fellowship medications epilepsy 200ml liv 52 amex, training or career de velopment programs. Further, over the period encompassing 2000 to 2004 there was a decrease in the number of career development awards. Given all this, the field is ripe for expansion, but there are too few young and midcareer investigators. Attracting, training, and supporting investigators in sleep-related research is critical for fueling the scientific ef forts needed to make important discoveries into the etiology, pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment of chronic sleep loss and sleep disorders. Further, it is also important to train individuals whose major role will be master clinician, organizer and manager of care, and clinician-educator. In 2004, there were only 151 researchers who had a clinical sleep-related research project grant (R01) and only 126 investigators focused primarily on basic sleep-related research projects. It is, therefore, of critical importance that further investment be made to expand the number of well-trained in vestigators in the field. Many of the strategies described in Chapter 5 to increase the awareness among health care professionals will also likely attract new investigators into the field. These strategies include targeting the career interests of high school and college students, as well as graduate students and students in allied health fields. As a result of the current limited pool of senior investigators and concurrent clustering of senior people at a limited number of academic centers, it will be equally important to adopt flexible mentoring programs that are capable of meeting the challenges. However, the current workforce is still not adequate, given the public health burden of the disor ders (Chapters 3 and 4). Clinical advances have helped to attract and increase the number of clinicians and scientists to somnology and sleep medicine, as evidenced by the growth of membership in professional sleep societies. How ever, the recent growth also emphasizes the need for a greater number of senior mentors and leaders in the field. Therefore, there are still substantial deficiencies in the workforce needed to address clinical somnopathy, and needs may be even greater relative to investment in research. Growth in sleep-related research is limited by the paucity of funded investigators in the field. Although there has been an increase in the number of investigators since 1995, in comparison to other disorders, there are still too few sleep researchers. For instance, the absolute number of funded in vestigators with sleep-related projects is only around 80 percent of fields 2 such as asthma, which is a single disorder that affects 20 to 40 million. However, in 2004, the average age of recipients at the time of their first R01 sleep-related grant was 51 (personal communication, M. The limited number of researchers is clustered at a limited number of institutions. Of the 253 funded primary investigators in 2004, 33 percent of all investigators were at the top 10 academic sleep programs (ranking by the total number of somnology and/or sleep disorders grants), and 60 per cent of all investigators were at the top 25 institutes (Appendix J). Likewise, 34 percent of all sleep-related R01 grants are awarded to the top 10 sleep 2314 individuals with asthma grants were identified by analyzing all 2004 R01 grants. Asthma grants were identified by all R01 grants that contained the word asthma as a thesaurus term. It is important to note that because only one search term was used, this search was not as thorough as the search performed for somnology and somnopathy R01 grants. Therefore, it may represent a significant under representation of the asthma field. In 2004, Harvard University, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Pittsburgh received 46 percent of sleep-related career development awards. Further, although many sleep disorders dispropor tionately affect minorities (Rosen et al. In 2004, only 15 percent of all investigators with an R01 identified themselves as belonging to a minority ethnicity (Asian, African American, Hispanic, Pacific Islander, or other) (personal communication, M. As minority clinicians and investi gators are more likely to work in underserved areas (Urbina et al. Barriers to Sleep Research Career Development Barriers to attracting, training, and sustaining a critical mass of sleep investigators include the poor awareness among the general public and health care professionals and the availability of appropriate mentors to pro vide scientific and career guidance to new investigators. Exciting basic science research and the dissemination of this excitement to a broad group of potential trainees are necessary and potentially rate limiting steps in attracting new investigators from a limited pool of indi viduals committed to academic careers. There fore, although there have been some remarkable successes in scientific in vestigation aimed at elucidating fundamental sleep physiology and biology. Fundamental scientific discoveries play critical roles in galvanizing interest in any scien tific discipline. Recruiting and retaining trainees in somnology and sleep medicine competes with other more established fields, many of which have made highly publicized advances, enjoy widespread respect across medical centers, and are more established as an academic discipline. Resource allocation needed to support new investigators may require complex negotiations among academic departments, which may deter new investigators or otherwise limit their access to needed support. In addition, identification of optimal mentoring relationships, critical for career development, will likely require sustained relationships among individuals with competing institutional commitments. Increasing fiscal pres sures and, for physicians, demands to spend more time on clinical services, are threats to protected time critical for career development. New investiga tors are also often burdened with substantial debt from school loans, pro viding disincentives to participate in prolonged postdoctorate training. Programs have been developed with the aims of attracting new trainees and developing the research and academic skills, and supporting their transition to independent and externally funded investigators (K01, K02, K08, K23, and K25). National Research Service Award Institutional Training Grants (T32) provide institutions with funds to support the training of individual postdoctoral candidates. This database collects informa tion on the number of federally funded biomedical research projects. To limit the number of grants that were not relevant to somnology or sleep disorders, the committee included only grants in which the key words appeared in both the thesaurus terms and the abstract and not the abstract alone. Analysis of the number of sleep-related T and F awards shows an increase between 2000 and 2004 ure 7-2). However, the number of K awards decreased over the same time period and a larger proportion went to a smaller group of academic institutions. Three institutions, Harvard University, Univer sity of Pennsylvania, and University of Pittsburgh, accounted for 27 per cent of all sleep-related T, K, and F grants received in 2000, 35 percent in 2004. The same three institutions received 29 percent of all K awards in 2000, and 46 percent in 2004. This may reflect the extensive develop ment of these programs and concentration of senior investigators. In general, for any given award category, with few exceptions no more than one new career development award was granted in any given year between 2000 and 2004. Since 2000, investment in career development awards for clinical scientists, K08 and K23, has var ied. Although there has been greater investment in the K23 series, it is still minimal with five new awards in 2003 by four different institutes. There has also been very limited investment in the K07 academic career awards, designed to improve curricula and emphasize development of scien tist leadership skills. Apart from the Sleep Academic Award program, there has been very little investment through the K07 mechanism, no new awards were granted in 2003, and only three in 2004. Over the 5-year period between 2000 and 2004, there has been even less investment in career development awards for mentored research (K01), independent scientists (K02), and senior scientists (K05). All three of these mechanisms historically have been used to support basic research. In 2004, these numbers have decreased to two K01 awards, two K02 awards, and one K05 award. Although the decrease in career development awards is dramatic, it is important to note that over the same period, there has been an increase in fellowship awards (Appendix I). The underlying reasons may be multiple, including poor or low numbers of applications, insufficient sleep-related research expertise on study sections (which is also partially affected by a limited number of senior mem bers of the field), and lack of awareness of the extent of the problem. Further, K awards are expensive; consequently, institutes are often reluctant to invest heavily in the K awards, especially in periods of budget constraints. If four institutes were to cosponsor a K23 program in somnology or sleep medicine, this would cost each insti tute approximately $34, 000 annually per award, a 75 percent decrease in expense. The committee strongly recommends joint investment in training programs; it does so recognizing that there are potentially increased over head costs associated with tracking and implementing an annual transfer of funds between institutes. Further, mechanisms need to be developed to en able all institutes contributing to a joint effort to be acknowledged in con gressional goals for new grants. These initiatives emphasize translational research, behavioral/social sciences, and quantitative sciences. Each initiative is designed to facilitate postdoctoral fellows into independent faculty positions. The initial phase (K99) is a 1 to 2-year mentored period designed to allow investigators to complete their supervised research work, publish results, and search for an indepen dent faculty position. The second mechanism is an inde pendent research grant program, which does not require preliminary data. The final initiative is to speed up the R01 grant application turnaround time for new researchers who fail to receive an award on their first attempt. There are alarming downward temporal trends in level of sup port for research training and career development, suggested by the recent drop in funded K awards, with further clustering of funding to fewer insti tutions. Institutes that support large levels of sleep research funding should also be encouraged to make a significant investment in career development initiatives. Funding trends also suggest that there are very few individuals with training support to develop careers in basic sleep science. There are many existing training grants or large research programs in disciplines re lated to somnology or sleep medicine. Given the interdisciplinary nature of the field, these programs provide an additional mechanism for increasing the number of somnology and sleep medicine trainees. Although there is an exciting national movement toward supporting interdisciplinary and trans lational research highlighted in roadmap initiatives, existing programs largely have not recognized the potential of the somnology and sleep medi cine field as a prototype for these initiatives. This represents a great oppor tunity to both foster development of sleep research and to forge new inter disciplinary approaches. Well-established car eer training awards are available from professional organizations with interest in somnology and sleep disorders, such as the American Heart As sociation, American Diabetes Association, American College of Chest Phy sicians, American Lung Association, and the American Thoracic Society, among others. Table 7-1 shows the number of career development awards several organizations made in 2004. Since sleep-related research is relevant to several of these organizations, the number of sleep-related training grants is also provided. One im pediment leading to the limited support from these organizations is that they might not recognize the important role they have in fostering interdis ciplinary research, as they are focused on more traditional organ-based research. From 2003 to 2005 the program received on average 18 applications (per sonal communication, R. Foundations, such as the Francis Family Foundation, have made no table contributions to training pulmonary scientists through the Parker B. Over the last 30 years, this foundation has contributed nearly $40 million in support of more than 600 fellows, some of whom have worked in the somnology and sleep medicine field. Each award is for 3 years, and provides stipends, fringe benefits, and travel ex penses to postdoctoral fellows or newly appointed assistant professors to enable their research development related to pulmonary disease and lung biology. A survey of former fellows demonstrated that greater than 90 per cent of respondents are currently employed in academic settings and spend a significant portion of their time on research. Summary of Foundation Support of Career Development Programs Given the overall paucity of support, further investment is required by private foundations for career development. Francis Foundation and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (Box 7-1) are excellent models of sustained foundation support for research career development. Although professional organizations cannot directly support research fellowships, through associated foundations they have made moderate to large investments in research career development, in cluding funding for some trainees with a primary somnology and somno pathy focus. Funds for these programs have been derived from endow ments and well-organized, targeted fund-raising efforts. This analysis identifies the potential availability of funding for sleep training from multi and interdisciplinary initiatives available through professional organiza tions with secondary interests related to sleep loss and/or sleep disorders, in addition to the need for organizations with primary sleep-related agen das to invest more heavily in developing the next generations of investiga tors. Despite the relative rarity of this condition in the population (30, 000 children and adults), and the relatively small pool of researchers available to recruit from, foundation support has succeeded in developing a cadre of pro ductive researchers, who largely have a strong history of sustained aca demic contributions. Three key programs have been developed through the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation: the Clinical Fellowship Program, the LeRoy Mathews Program, and the Harry Shwachman Fellowship. To gether, these programs provide support for the full spectrum of trainees: combined clinical/research fellowship training, early research career de velopment (enrolling fellows within the first 4 years of training), and junior faculty development. Support for these programs is derived from well organized fund-raising and philanthropy. The combined support for these training programs represents approximately 2 percent of the annual Cystic Fibrosis Foundation budget. The Clinical Fellowship Programs expose fellows early in their train ing to working in a multidisciplinary team environment. It supports first and second years for the clinic, and during the third and fourth year supports time for basic, translational, or clinical research. Fellows re ceive an annual base salary of $52, 000 with an additional $10, 000 for research supplies.