Doxycycline

Mark D. Kilby MD MRCOG

- Professor in Maternal and Fetal Medicine, Division of

- Reproduction and Child Health, Birmingham Women?

- Hospital, Birmingham

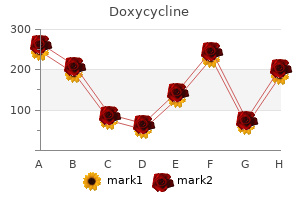

Despite significant increases from pre-test to post-test in the percentage of participants who believed cervical cancer was preventable bacteria for kids purchase doxycycline mastercard, almost half of women (44%) at post-test still believed cervical cancer was not preventable antibiotic resistance review article buy 100 mg doxycycline free shipping. These results highlight the need to increase education efforts that promote the benefits of screening and address women’s anxieties about the procedure in ways that will motivate and keep them engaged in cervical cancer prevention infection examples cheap 200 mg doxycycline fast delivery. The negative experiences with the public health system antibiotic resistance and public health discount generic doxycycline uk, coupled with fear of testing and limited knowledge of the effectiveness of prevention efforts virus 7th grade science buy cheap doxycycline on line, may make women less likely to seek screening oral antibiotics for acne minocycline buy 100mg doxycycline mastercard. Although we made an effort to provide women with a wide list of choices for potential reasons why they have not sought screening, we found many women had difficulty fitting their experiences into those categories, and the most frequently selected answer for not screening was “other”. It is important to understand the context under which Jamaican women fail to seek cervical cancer screening. Future studies may consider adopting a qualitative approach, as the open-ended nature of qualitative research yields extensive narratives that may provide a more comprehensive picture of women’s experiences, helping inform the development of future interventions to promote screening. Over one third of participants reached post-intervention had screened for cervical cancer. Almost half of women reached who never screened pre-intervention—and over a third of women Int. Public Health 2016, 13, 53 9 of 11 reached with a screening history pre-intervention—moved to the action Stage of Change and screened for cervical cancer. These results suggest our intervention successfully motivated screening-naïve women to adopt the positive behavior change and reach levels akin to women who had screened previously. However, movement through the Stages of Change has been found to be cyclical [23], requiring several efforts before individuals may reach their goals, thus women will likely need further support to help them maintain the behavior change. Studies have shown healthcare provider recommendations may positively influence uptake of cervical cancer screening [3,16,24]. There is a need for a comprehensive strategy to educate women about cervical cancer and reduce barriers to facilitate engagement in screening and follow-up care after receiving abnormal test results. As doctors and nurses are already the principal source of cervical cancer screening knowledge for women in the study (Table 2), providers may play a pivotal role in encouraging women to adopt protective health behaviors, dispelling misconceptions of screening tests, and providing comprehensive health education to keep women engaged in their health. Responses to questions such as intention-to-screen may be biased due to social desirability, and may have differed had screening tests been available immediately following the intervention. Issues with incomplete surveys reduced our sample size, however we do not believe this compromised the significance of our finding as we still obtained a sample representative of the population in the four western parishes sampled. Lastly, budget and time constraints did not allow for long-term follow-up of participants to assess long-term effects of the intervention on participant cervical cancer knowledge and screening behavior. Conclusions the use of a theory-based educational intervention significantly increased knowledge of cervical cancer risk factors, symptoms, and screening tests, and resulted in almost one half of participants contacted seeking screening post-intervention. Our results demonstrate the ability of an educational intervention to reduce barriers and elicit positive cervical cancer screening behavior, and may contribute to future efforts to increase cancer-screening rates in similar low-resource settings. Future research focusing on healthcare providers is needed to assess provider knowledge, attitudes, practices and training regarding cervical cancer screening. Health officials should also develop recommendations for enhancing healthcare worker capacity to promote cervical cancer education, screening and adherence to follow-up care. We thank the health educators of the Epidemiology Unit at Cornwall Regional Hospital, Western Regional Health Authority, and Kyaw Lwin for their invaluable assistance in the implementation of this study. Jolly, and Maung Aung designed the research; Evelyn Coronado Interis and Chidinma P. Anakwenze performed the research with assistance from Maung Aung; Evelyn Coronado Interis analyzed the data; Evelyn Coronado Interis and Chidinma P. Determinants of adequate follow-up of an abnormal Papanicolaou result among Jamaican women in Portland, Jamaica. Knowledge attitudes and practices of cervical cancer screening among urban and rural Nigerian women: A call for education and mass screening. Jamaica Health and Lifestyle Survey 2007–2008; University of the West Indies: Mona, Jamaica, 2008; p. Factors affecting uptake of cervical cancer screening among clinic attendees in Trelawny, Jamaica. Perception of women on cancer screening and sexual behavior in a rural area, Jamaica: Is there a public health problem? Demographic, knowledge, attitudinal, and accessibility factors associated with uptake of cervical cancer screening among women in a rural district of Tanzania: Three public policy implications. Determinants of acceptance of cervical cancer screening in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Evaluating a theory-based health education intervention to improve awareness of prostate cancer among men in western Jamaica. Breast and cervical cancer screening in Hispanic women: A literature review using the health belief model. Effect of a media-led education campaign on breast and cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese-American women. Predictors of cervical Pap smear screening awareness, intention, and receipt among Vietnamese-American women. Panel members American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and the were given the opportunity to submit questions both before and American Society for Clinical Pathology substantially updated screening after the discussion. Additional questions, recommendations, and discussion A 2014 publication by Ronco et al. A recent found in women between 25 and 29 years of age and 37% of cases were studypublishedbyHopenhaynet al. Data in this Transitioning from current guidelines for 21–24 year olds requires area are limited and further research is necessary. Ault also has Primary cervical cancer truly negative for high-risk human papillomavirus is a rare been a consultant to the National Cancer Institute and the American College of Obstetri but distinct entity that can affect virgins and young adolescents. Garcia received no per type distribution in 30,848 invasive cervical cancers worldwide: variation by geo sonalcompensation. Please ensure that you lodge the data you gather there (see page 56 for guidance). Test retest reliability over a 1 week interval was found to be good, with all correlations above 0. Participants who received the intervention leaflet consistently obtained higher scores than those who received the control leaflet. If it is not possible to use either of these methods we advise using a supervised self-complete method where individuals are asked to complete the measure but under supervised conditions with someone available for guidance. For example, you should be aware that not everybody will have internet access, and in particular those from lower socio-economic groups may not have access. You should ask respondents to ensure that they are not to be distracted by anyone while completing the survey. Q1 and Q5 are ‘unprompted’ questions which ask respondents to recall warning signs or risk factors from memory. Q2 and Q6 are ‘prompted’ questions asking respondents to respond to a prompted list of warning signs and risk factors. If you are interested in what people actually ‘know’ you should keep the unprompted questions. But if you would prefer to assess respondent’s ability to ‘recognise’ signs or risk factors, you should keep the prompted questions. Ethical approval Before you start recruiting your sample, please consider whether you need to obtain ethical approval, this is usually stipulated by the organisation that is funding the research. Regardless of the type of research you are doing it is always appropriate to consider the ethical implications. This is especially important when you are asking people for identifiable information such as their postcode. We have developed an example information sheet and consent form that you can use and modify to your own needs (see page 11). Ensuring quality Whether you plan to carry out the survey using volunteers or by commissioning an external agency you should ensure that the research is good quality. Please name as many as you can think of ” this is an open question designed to measure how many cervical cancer warning signs a respondent can recall unaided. We are interested in your opinion ” these closed questions are designed to measure how many warning signs a respondent can recognise when prompted. Q5 – Open risk factors (unprompted) “What things do you think affect a woman’s chance of developing cervical cancer? Q6 – Closed risk factors (prompted) “The following may or may not increase a woman’s chance of developing cervical cancer. If you do decide to take part you will be given this information sheet to keep and be asked to sign a consent form. If you decide to take part, the survey will take approximately [xx] minutes to complete. I understand that other researchers may use my words in publications, reports, web pages, and other research outputs according to the terms I have specified in this form. Please name as many as you can think of: Cervical Cancer Awareness Measure Toolkit Version 2. We are interested in your opinion: Yes No Don’t know Do you think vaginal bleeding between periods could be a sign of cervical cancer? Do you think a persistent vaginal discharge that smells unpleasant could be a sign of cervical cancer? Do you think menstrual periods that are heavier or longer than usual could be a sign of cervical cancer? Do you think vaginal bleeding during or after sex could be a sign of cervical cancer? If yes, at what age are women first invited for cervical cancer screening in England? White Mixed Asian or Asian Black or Black Chinese/other British British White British White and Indian Black Chinese Black Caribbean Caribbean White Irish White and Pakistani Black African Other Black African Any other White and Bangladeshi Any other Prefer not to White Asian Black say background background Any other Any other Mixed Asian background background 4. No Yes, one Yes, more than one Prefer not to say Cervical Cancer Awareness Measure Toolkit Version 2. Yes No Don’t know Prefer not to say If you plan to use the following question we advise piloting it first with the target group to ensure that it is not off-putting. From: (dd/mm/yyyy) to: (dd/mm/yy) Cervical Cancer Awareness Measure Toolkit Version 2. If you are interviewing people face-to-face it may be useful to use ‘prompt cards’ for some of the questions. Do not prompt If the respondent asks for clarification about certain items within this set of questions, please refer to the clarifications written below. Do you think a persistent pain in your abdomen could be a sign of cervical cancer? Write down all of the risk factors that the person mentions exactly as they say it. How much do you agree that each of these can increase a woman’s chance of developing cervical cancer? You will not be asked your name and all of your answers will be kept strictly confidential and anonymous. The correct answers to this question are listed in question 2, although there are other warning signs and symptoms and none of the signs and symptoms listed would necessarily be caused by cancer. People are first invited to attend cervical cancer screening at age 25 in England. Face-to-face 1 Telephone 2 Internet 3 Other 4 Please indicate where the survey was completed. InterviewSetting If ‘Other’ (code 3) create an additional variable ‘InterviewSettingOther’ and write the response verbatim. InterviewLanguage If ‘Other’ (code 7) create an additional variable ‘InterviewLanguageOther’ and write the response verbatim. English 1 Sylheti 5 Urdu 2 Cantonese 6 Punjabi 3 Other 7 Gujarati 4 Cervical Cancer Awareness Measure Toolkit Version 2. Cervical symptom14, Ovarian symptom15 etc and write the response the participant has given verbatim. Cervical vaginalbleedC Do you think persistent lower back pain 3 2 1 could be a sign of cancer? Cervical heavyperiodsC Do you think persistent diarrhoea is a sign 3 2 1 of cervical cancer? Cervical diarrhoeaC Do you think vaginal bleeding after the 3 2 1 menopause is a sign of cervical cancer? Cervical bleedingmenopauseC Do you think persistent pelvic pain could be 3 2 1 a sing of cervical cancer? Cervical pelvicpainC Do you think vaginal bleeding during or 3 2 1 after sex could be a sign of cervical cancer? Cervical bleedduringaftersexC Cervical Cancer Awareness Measure Toolkit Version 2. Cervical bloodinstoolC Do you think unexplained weight loss could 3 2 1 be a sign of cervical cancer? Variable Scoring A woman aged 20 to 29 years 1 A woman aged 30 to 49 years 2 A woman aged 50 to 69 years 3 A women aged 70 or over 4 Cervical cancer is unrelated to age 5 Refusal 98 Cervical Cancer Awareness Measure Toolkit Version 2. Variable name; Cervical symptomConfidence Not at all Not very Fairly confident Very confident Refusal confident confident 1 2 3 4 98 8. Language To code a language that is not on the list code as ‘Other’ (code 7) and write the language verbatim in ‘OtherLanguage’ 1 English 5 Sylheti 2 Urdu 6 Cantonese 3 Punjabi 7 Other. Are you currently: Employed 1 Employed full-time 5 Full-time homemaker 2 Employed part-time 6 Retired 3 Unemployed 7 Still studying 4 Self-employed 8 Disabled or too ill to work 98 Prefer not to say 11. Yes No Don’t know Prefer not to say You 1 2 3 98 CancerYou Partner 1 2 3 98 CancerPartner Close family member 1 2 3 98 CancerCloseFamily Other family member 1 2 3 98 CancerOtherFamily Close friend 1 2 3 98 CancerCloseFriend Other friend 1 2 3 98 CancerOtherFriend Cervical Cancer Awareness Measure Toolkit Version 2.

Syndromes

- Dislocated shoulder

- Blood clots in the legs that may travel to your lungs

- Partial: The placenta covers part of the cervical opening.

- Breathing tube

- Injury to the common bile duct

- Trim the toenails about once a month.

- Bluish skin color, called cyanosis (the lips may also be blue), due to low oxygen in the blood flowing to the body

- Severe abdominal pain

Specimen Orientation If the specimen is the product of a cone biopsy or an excisional biopsy antibiotic used to treat cellulitis buy doxycycline uk, it is desirable for the surgeon to orient the specimen to facilitate assessment of the resection margins (eg virus removal free purchase doxycycline overnight delivery, stitch at 12 o’clock) antibiotic dental prophylaxis purchase doxycycline toronto. In these cases antibiotic nitro buy doxycycline now, the clock face orientation is designated by the pathologist and is arbitrary antibiotic resistance china cheap doxycycline express. Each tissue section may be marked with India ink or a dye such as eosin in order to orient embedding and facilitate evaluation of margins infection during labor cheap doxycycline 100 mg without prescription. For optimal evaluation, the sections are placed into separate cassettes, which are numbered consecutively. Absence of Tumor If no tumor or precursor lesion is present in a cytology or biopsy specimen, the adequacy of the specimen (ie, its content of both glandular and squamous epithelium) should receive comment. The absence of tumor or precursor lesions in resections must always be documented. If the invasive focus or foci are not in continuity with the dysplastic epithelium, the depth of invasion should be measured from the deepest focus of tumor invasion to the base of the nearest dysplastic crypt or surface epithelium. If there is no obvious epithelial origin, the depth is measured from the deepest focus of tumor invasion to the base of the nearest surface epithelium, regardless of whether it is dysplastic or not. These should not be regarded as in situ lesions and the tumor thickness (from the surface of the tumor to the deepest point of invasion) should be measured in such cases. If it is impossible to measure the depth of invasion, eg, in ulcerated tumors or in some adenocarcinomas, the tumor thickness may be measured instead, and this should be clearly stated on the pathology report along with an explanation for providing the thickness rather than the depth of invasion. When more than 1 block is involved, it is the product of the number of consecutive blocks with tumor and thickness of a block. A recent publication by Day et al states that multifocal tumors should be defined as invasive foci separated by a tissue block within which there is no evidence of invasion or as 12 Background Documentation Gynecologic. They recommend that multifocal tumors should be staged based on the largest focus. If a margin is involved, whether endocervical, ectocervical, deep, or other, it should be specified. The severity and extent of a precursor lesion (eg, focal or diffuse) involving a resection margin of a cone should be specified. At times, it may be difficult to determine whether vascular/lymphatic vessel 5 invasion is present; in such cases, its presence should be categorized as indeterminate (cannot be determined). In these cases, the extent of tumor involvement of the urinary bladder and rectum and the relation of the tumor to the cervical carcinoma should be described. The entire specimen can then be hemisected through the neoplasm, and appropriate sections can be obtained. Pathologic staging is usually performed after surgical resection of the primary tumor. Pathologic staging depends on pathologic documentation of the anatomic extent of disease, whether or not the primary tumor has been completely removed. The “y” categorization is not an estimate of tumor prior to multimodality therapy (ie, before initiation of neoadjuvant therapy). Additional Descriptors Residual Tumor (R) Tumor remaining in a patient after therapy with curative intent (eg, surgical resection for cure) is categorized by a system known as R classification, shown below. For the pathologist, the R classification is relevant to the status of the margins of a surgical resection specimen. There is currently no guidance in the literature as to how these patients should be coded; until more data are available, they should be coded as “N0(i+)” with a comment noting how the cells were identified. There is little data to assign risk for nonsentinel lymph node metastasis based on the size of the metastasis in the sentinel lymph node. Distinction between endometrial and endocervical adenocarcinoma: an immunohistochemical study. Kostrikis 1,* 1 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Cyprus, 1 University Avenue, Aglantzia 2109, Nicosia, Cyprus; Chrysostomou. Since the development of the Papanicolaou (Pap) test, screening has been essential in identifying cervical cancer at a treatable stage. Accordingly, comparative studies were designed to assess the performance of cervical cancer screening methods in order to devise the best screening strategy possible. Introduction Cancer of the cervix uteri, more commonly known as cervical cancer, is an important public health concern. It was reported as the fourth most frequently occurring gynecological cancer, with an estimated worldwide incidence of 528,000 cases and 266,000 deaths in 2012 [1]. In Europe, an estimated 58,373 women are diagnosed annually with cervical cancer, and 24,404 of those die from this illness [2]. The incidence and mortality of cervical cancer, however, have been declining in developed countries due to the discovery of the Pap test in the 1940s, which enabled the prompt identification of morphological changes in the cervical epithelium [3]. The use of the Pap test in national screening programs can be dated back to the 1960s and 1970s [4], and it is still a cornerstone in the majority of current programs. These viruses have a genome of 8 kb that encodes early regulatory proteins (E1, E2, E5, E6, and E7), and late structural proteins (L1 and L2). According to estimates, approximately 80% of sexually active women will acquire the infection in their lifetime, and in the majority of cases (>90%), it will be a transient, asymptomatic infection cleared by the immune system in six months to two years [17–19]. Furthermore, in accordance with recommendations specified in the recent European Guidelines, important aspects of screening programs necessary for the success and efficiency of such systems are highlighted. Finally, the current landscape of cervical cancer screening programs of member states of the European Union (E. Conventional Pap Test and Its Alternatives Testing to identify anomalies in the cervix can be dated as far back as the early 19th century, when anatomists and pathologists of the time observed and studied the cytological changes derived from cervical and other genital neoplasms, as well as the woman’s menstrual cycle [27]. In the mid-1800s, the Irish physician Walter Hayle Walsh was the first to show that cancerous cells could be identified by microscopy [28,29]. In the early 20th century (1927), the Romanian physician Aurel Babe¸s detected the presence of cervical cancer by collecting cells from a woman’s cervix using a platinum loop and then observing them under a microscope. Traut, cervical cytology gained a robust and low-complexity method of screening for cervical cancer [30]. This process entails the exfoliation of cells from the cervix, which are then fixed, viewed under a microscope, and are subsequently morphologically interpreted. The staining method developed for this test offered a polychromatic definition of the nucleus and the features of the cytoplasm. The Pap test allows the assessment of nuclear chromatin alterations to discern whether necrosis occurred, the observation of the degree of cellular degeneration, and the distinction of the maturity of squamous epithelial cells [28,30,31]. Despite its widespread use as the primary cervical cancer screening method, the Pap test has some important limitations. The staining procedure of the conventional Pap test requires a considerable amount of time (20–30 min) and consumables [32]. The smearing process of the Pap test is also Viruses 2018, 10, 729 3 of 35 characterized by poor reproducibility and is vulnerable to obscuration by blood and mucus, imperfect fixation, and a non-uniform distribution of cells, thus causing errors in the detection and interpretation of the results. These issues can be attributed partly to the quality of sampling and can explain the broad range of sensitivity (30–87%) reported for the Pap test [33,34]. These modifications significantly improved upon the conventional Pap smear performance in terms of speed and cost, and are also more environmentally friendly. The guiding principle of these enhancements was to improve at least one aspect of the smear without compromising the quality of the results [32,35–38]. This method entails the collection of cells from the cervix, which are then transferred to a vial containing preservative solution instead of being fixed on a slide, thus enabling uniform distribution of the collected clinical material. These techniques are based on the fact that upon the application of acetic acid or Lugol’s iodine directly to the cervix, precancerous cervical lesions become discernible to the naked eye by both clinicians and nonclinicians. Cervical cytology has undoubtedly played an important role in cervical cancer screening and continues to do so. However, it has inherited the limitation of being a morphological method requiring subjective interpretation by well-trained cytologists [11]. Consequently, when they are used for agreed clinical indications they can yield a large number of clinically insignificant positives, resulting in more false referrals for colposcopy and biopsy, decreased correlation with the histological presence of disease, unnecessary treatment of healthy women and a consequent distrust of a positive result by the treating physician. In addition, it should always be taken into consideration that absolute reassurance following a negative cervical cancer screening test result is not achievable at any analytic sensitivity, because of a myriad of factors that are independent of the actual screening test performance, including operator error and poor cervical sampling. It can be expected that several previously approved tests will eventually be validated for use with the most commonly used collection media [58]. With this knowledge, it became clear that stopping hr types of the virus from ever infecting should be explored as an option, in addition to the preexisting cervical cancer screening tests. Currently, for all three vaccines two doses are recommended for persons starting the series before their 15th birthday and three dose schedule for those who start the series on or after their 15th birthday and for persons with certain immunocompromising conditions [71]. Decreasing the number of doses not only leads to reductions in overall cost, which is a concern (especially in low-income countries), but it also increases adherence to the program [71–73]. Organization of Screening With extensive knowledge of the biology of cervical cancer and with an arsenal of screening and prevention tools, the disease can be detected at an early enough stage to be curable. As a concept, the fundamental principles of cervical cancer screening can be dated back as far as the 1940s, before organized screening programs took place [4,77]. However, it was not until 1968 that Wilson and Jungner defined a set of criteria (comprehensively reviewed by Basu et. Undertakings of such magnitude, however, are no trivial tasks, since a number of prerequisites have to be accounted for before embarking on the implementation of such programs. The nature and parameters of the program, which are directly influenced and supported by scientific progress, must be established [47,78]. To this end, the first edition of the European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Cervical Cancer Screening, published in 1993 [79], designated the principles for organized, population-based screening, with a number of countries adhering to this recommendation [80]. The supplements of the second edition of the European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Cervical Cancer Screening of 2015 (the original volume of the second edition was published in 2008) emphasize the importance of the implementation of an organized, population-based cervical cancer screening program with a call/recall invitation system in order to take full advantage of the benefits of screening and discuss the key aspects of this type of organization in considerably increased detail [55,80]. Such a program should have a national/regional team that directs the implementation of guidelines, rules and procedures. Viruses 2018, 10, 729 7 of 35 this team would also be responsible for quality assurance to monitor and to guarantee that all levels of the process are performed sufficiently. This responsibility includes the management and coordination of the call/recall system, testing and diagnosis, as well as follow-up after positive test results. Furthermore, quality assurance procedures call for attention to training personnel, evaluating performance, auditing and monitoring, and reviewing the impact of the program on the burden of disease. The latter is facilitated by the population-based nature of the program, which is characterized by the identification and personal invitation of each member of the targeted population eligible for screening [6,81,82]. In contrast to organized population-based screening, opportunistic screening depends on the initiative of the individual woman and/or her doctor. This type of screening often results in high coverage only in certain parts of the population, which are screened frequently, while other parts of the population, usually with a lower socioeconomic status, exhibit lower coverage. This situation results in uneven coverage with heterogeneous quality, limited effectiveness, and reduced cost-effectiveness, as well as difficulty in monitoring the population [81]. Thus, as the European Guidelines recommend, a program with an organized population-based nature may substantially improve the accessibility and equity of screening access while simultaneously improving effectiveness and cost-effectiveness [6,81]. The key factors to be specified within such a program are the target age, screening intervals, and screening algorithm. The latter refers to the primary screening test and the subsequent management of results at each step of the algorithm. Cytology-based testing has been used for primary screening for more than half a century and is currently employed by the majority of screening programs in Europe. As described earlier in this review, cytology-based testing has various technical characteristics that affect its standing at the forefront of screening. It has undoubtedly proven its impact on reducing cervical cancer morbidity and mortality, especially in organized settings [84]. However, the low sensitivity of the technique, the requirement for high-quality diagnostic facilities, the high costs needed to sustain the infrastructure, and the need for highly trained personnel are important issues that have brought primary cytology screening under intense scrutiny for the past twenty years [85,86]. To maintain the accuracy and performance of cervical cytology, short intervals between screenings are required, which implies the performance of an increased number of tests and as such it can be costly [83]. Longer screening intervals contribute to less expensive programs, as well as providing a longer duration of “peace of mind” when women test negative in comparison to cytology-negative women [47,91]. Nonetheless, the avoidance of screening prior to the age of 20 is recommended [53,55,91]. Nonetheless, it is important to note that cytology performs relatively poor at those ages, especially for postmenopausal women, in whom epithelial atrophy is commonly observed. Moreover, the cervical transformation zones of postmenopausal women are situated in the cervical canal, making the collection of material for cytological examination less accessible. Accordingly, cytology has low sensitivity for postmenopausal women, and screening can result in elevated false-positive results [95,98]. Furthermore, 30% of cervical cancer cases were still diagnosed in women older than 60, with a mortality as high as 70%. These findings, coupled with the non-optimal performance of cytology in older women, suggest the extension of the screening age as well as the need for more research [98]. The same sample used for primary testing is recommended to be subsequently used for triage testing in order to reduce the risk of follow-up loss and maximize the efficiency of resources [47,55,91,99]. However, at this time, there are insufficient data to favor such methods over cytology for triaging in Europe. Methylation is in a similar predicament: it is still in the early stages but is displaying great potential as an accurate and promising molecular risk-stratification marker. The objectivity that this method offers, the consistency, and the high throughput potential will make methylation a strong candidate triaging method even if its performance is equivalent to that of cytology [55,101,102]. The open issue is how to select the most Viruses 2018, 10, 729 10 of 35 appropriate follow-up test and intervals for repeat testing. The European Guidelines report that at present the evidence available is not sufficient to definitively recommend a single approach for all settings [55] and as such provide three strategies for repeat testing (Figure 1). This algorithm was developed based on “The supplements of the or more severe cytological result. This algorithm was developed based on “The supplements of thesecond edition of the European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Cervical Cancer Screening of second edition of the European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Cervical Cancer Screening of2015”[55].

Cheap doxycycline 200 mg overnight delivery. How to care for a healing wound.

We now add opiates to our local anesthetic solutions which have many benefits but also add to the list of complications zeomic antimicrobial buy doxycycline. We have learned a great deal about the physiology of spinal anesthesia in the last 50 years thanks to outstanding contributions made by Sir Robert Macintosh and Professor Nicholas Greene infection 2 walkthrough purchase doxycycline 200mg amex. It is very likely that anesthesiologists will still be performing spinal anesthesia 100 years from now do topical antibiotics for acne work purchase doxycycline 100mg online. We owe a debt of gratitude to Bier and Hildebrandt for the gift of spinal anesthesia antibiotics for acne results doxycycline 100mg mastercard. Incidence and causes of failed spinal anesthetics in a university hospital: a prospective study antibiotics vertigo order doxycycline without prescription. A retrospective study of the incidence and causes of failed spinal anesthetics in a university hospital antibiotics for sinus infection azithromycin order doxycycline with paypal. A retrospective analysis of failed spinal anesthetic attempts in a community hospital. Incidence and etiology of failed spinal anesthetics in a university hospital: a prospective study. Comparison of Sprotte and Quincke needles with respect to post dural puncture headache and backache. Influence of the injection site (L2/3 or L3/4) and the posture of the vertebral column on selective spinal anesthesia for ambulatory knee arthroscopy. Acute progesterone treatment has no effect on bupivacaine-induced conduction blockade in the isolated rabbit vagus nerve. Identification of patients in high risk of hypotension, bradycardia and nausea during spinal anesthesia with a regression model of separate risk factors. Bradycardia and asystole during spinal anesthesia: a report of three cases without mortality. Sudden asystole in a marathon runner: the athletic heart syn drome and its anesthetic implications. Prevention of hypotension following spinal anesthesia for elective caesarean section by wrapping of the legs. Placental blood flow during cesarean section performed under subarachnoid blockade. Cardiac arrest during neuraxial anesthesia: frequency and predisposing factors associated with survival. Effects of anaesthesia on postoperative micturition and urinary retention [French]. Micturition disorders following spinal anaesthesia of different dura tions of action (lidocaine 2% versus bupivacaine 0. Intrathecal hyperbaric bupivacaine 3mg + fentanyl 10µg for outpatient knee arthroscopy with tourniquet. A comparison of psoas compartment block and spinal and general anesthesia for outpatient knee arthroscopy. Hyperosmolarity does not contribute to transient radicular irritation after spinal anesthesia with hyperbaric 5% lidocaine. The addition of phenylephrine contributes to the development of transient neurologic symptoms after spinal anesthesia with 0. Transient neurological symptoms after spinal anaesthesia with 4% mepivacaine and 0. A follow-up of 18,000 spinal and epidural anaesthetics performed over three years. Neurologic complications following spinal anesthesia with lidocaine: a prospective review of 10,440 cases. Transient neurologic toxicity after hyperbaric subarachnoid anesthesia with 5% lidocaine. Transient radicular irritation after spinal anaesthesia with hyperbaric 5% lignocaine. Transient neurologic deficit after spinal anesthesia: local anesthetic maldistribution with pencil point needles? Bilateral severe pain at L3-4 after spinal anaesthesia with hyperbaric 5% lignocaine. Prospective study of the incidence of transient radicular irritation in patients undergoing spinal anesthesia. Is transient lumbar pain after spinal anaesthesia with lidocaine influenced by early mobilisation? The influence of ambulation time on the inci dence of transient neurologic symptoms after lidocaine spinal anesthesia. Transient neurologic symptoms after spinal anes thesia with lidocaine versus other local anesthetics: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Irreversible conduction block in isolated nerve by high concentrations of local anesthetics. Concentration dependence of lidocaine-induced irreversible conduction loss in frog nerve. Cauda equina syndrome following a single spinal administration of 5% hyperbaric lidocaine through a 25-gauge Whitacre needle. Epinephrine increases the neurologic poten tial of intrathecally administered local anesthetic in the rat [abstract]. Nerve root inflammation demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging in a patient with transient neurologic symptoms after intrathecal injec tion of lidocaine. Local anesthetic neurotoxicity does not result from blockade of voltage-gated sodium channels. An in vitro study of dural lesions pro duced by 25-gauge Quincke and Whitacre needles evaluated by scanning electron micros copy. Magnetic resonance imaging of cerebro spinal fluid leak and tamponade effect of blood patch in postdural puncture headache. Epidural blood patch: evaluation of the volume and spread of blood injected into epidural space. Radiological examination of the intrathecal position of the microcathe ters in continuous spinal anaesthesia. Post-dural puncture headache in young adults: comparison of two small-gauge spinal catheters with different needle design. Comparison of three catheter sets for continuous spinal anesthesia in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty. Injection given variable distances below acromion measured as centimeters or finger breadths. Injection is given into the midpoint of a triangle formed by acromion and a line drawn laterally from the apex of the anterior axilla across the deltoid muscle, approximately 2 or 3 finger breadths below the acromion. Injection into the middle third of the deltoid muscle Cook, 2011 Deltoid Injection Localization Techniques Method Distances of Injection from Mid-acromion (mid-way from tip of acromion to deltoid tuberosity 1. Anthropometric study: 536 patients (283 males, 253 females), ≥ 65 yo Abduction shoulder to 60°, placing hand on the ipsilateral hip Inject at midpoint between acromion and deltoid tuberosity Injection above midpoint of acromion & deltoid tuberosity potential injury to Anterior branch of axillary nerve Subacromial/Subdeltoid bursa Subacromial (Subdeltoid) Bursa Avoid injecting below apex of anterior axillary line: Radial nerve & Avascular musculotendinous insertion Injection site Do not inject below Anterior Apex of Axillary Line. Left shoulder = higher adipose thickness Assuming 25 mm needle (and success is > 5 mm muscle penetration). Under penetration in 1% subjects; over penetration in 50% subjects Hypothesis for mechanical shoulder injuries. Injection leads to a “robust local immune and inflammatory response” Subacromial bursitis, Bicipital tendonitis, and Inflammation of shoulder capsule (Adhesive capsulitis) Bodor and Montalvo, 2006; Cook, 2015. Periosteal reactions and osteonecrosis reported Cook, 2015 Subachromial bursitis – synovial tissue inflammatory infiltrate and granulation tissue with mild fibrosis Uchida, et al. Paresis involving shoulder develops in hours to days Typically involves the following combination of nerves Motor: Long thoracic, Suprascapular, Anterior interosseous Sensory: Superficial radial, Lateral antebrachial cutaneous, Axillary (“soldier’s patch”) Pt may not notice paresthesia because of severe intense pain. Parsonage Turner Syndrome Neuralgic Amyotrophy Brachial Neuritis Motor Nerves Muscles Long thoracic Serratus anterior Suprascapular Supraspinatus, Infraspinatus Anterior Interosseous Pronator quadratus, Flexor pollicis longus, Flexor digitorum profundus (radial half) Sensory Nerves Distribution Superficial radial posterior forearm and hand Lateral antebrachial cutaneous radial forearm Axillary lateral shoulder Clinical Presentation van Eijk, et al. The recognition of gait as a complex, ‘‘higher-order’’ serves as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim and form of motor behavior with prominent influence of mental processes has been an GlaxoSmithKline and receives important new insight, and the clinical implications of gait disorders are increasingly research grants from Abbott being recognized. Better classification schemes, the redefinition of established entities Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, and Medtronic, Inc. Products/Investigational Summary: Gait disorders are directly correlated with poor quality of life and in Use Disclosure: creased mortality. Because gait is very sensitive to any insult to the nervous system, Drs Fasano and Bloem discuss the unlabeled use of donepezil its assessment should be carried out carefully in routine clinical practice. However, when cognitive enhancers and examining gait, clinicians should bear in mind that the clinical phenotype is the net stimulation of the pedunculopontine nucleus result of changes induced by the disease itself plus any compensations adopted by as a surgical indication the patient to improve stability. This review presents a clinically oriented approach to for the treatment of gait and gait disorders based on the dominant phenomenology and underlying pathophys postural disorders. Many characterize gait and its disorders congenital or perinatal psychomotor based on phenomenology and patho disturbances first manifest as a de physiology. Gait disor will cover the multidimensional strate ders are one of the most common gies to improve gait, aiming to improve problems encountered in neurologic mobility and reduce the incidence of patients, present in more than half of falls and fall-related injuries. Supplemental digital content: all nonYbed-bound patients ad Videos accompanying this ar 1 mitted to a neurologic service. Video legends begin reduced life span (due to a combina behavior consisting of three primary on page 1379. The eral information and selecting the strat and death from cardiovascular system also partici egies that guarantee dynamic stability underlying diseases. Brainstem and Spinal Cord Cortical locomotor output from the Suprasegmental Control premotor cortex and the supplemen Gait control is tightly connected with tary motor area is conveyed to the the attentive resources and other cogni brainstem locomotor centers via the tive domains that regulate the strategies basal ganglia. This first step is based on preplanning and execution of a complex motor task and is followed by a more automatic, synchronized, and rhythmic motor planning, which leads to continuous stepping. A gait cycle is defined as the period between successive points at which the heel of the same foot strikes the ground (figure illustrates the cycle of the right leg). The stance phase, during which the foot is in contact with the ground, occupies 60% to 70% of the cycle; remaining time is occupied by the swing time, which begins when the toes leave the ground (‘‘toe off’’) and, by definition, is equal in time to the single support time of the other leg. During up to 25% of the gait cycle, both feet are in contact with the ground (double-limb support). This cycle period can be virtually absent (as during running), increased (as during cautious/senile gait, weakness, or disequilibrium) or asymmetric (as during limping gait). Step length the distance covered during the swing phase of a given leg (ie, the distance between a toe off and the next heel strike of the same leg). Stride length the distance covered during a given gait cycle (ie, the distance between two consecutive heel strikes of the same leg). Step width the distance between the two feet at the perpendicular axis to the walking direction for a given step. Step height the maximum distance between the forefoot and ground during the swing time. The most important structures for control of locomotion and balance are the frontal cortex (supplementary motor area especially), basal ganglia, and the mesencephalic locomotor region (and particularly the pedunculopontine nucleus). Following the integration of cognitive, sensory, and limbic cortical inputs, the frontal cortex projects heavily to the brainstem, activating the structures important for both postural control and locomotion. These subcortical structures are modulated by the tonic inhibition exerted by the basal ganglia and cerebellum and exert a supraspinal control of spinal segmental reflexes and alpha motoneurons responsible for movement. Cautious gait perturbations; and A classification based on the dom is linked to the ‘‘fear-of-falling syn (4) gait impairment inant clinical phenomenology has drome’’ and ‘‘fall phobia,’’ which de 7 can be a secondary been proposed ; this review will be notes a heterogeneous syndrome epiphenomenon of guided by both phenomenology and clinically characterized by a dispropor disorders primarily pathophysiology (Table 8-3). Clinical Assessment of Reckless gait (also known as care h Antalgic gait is a Gait Disorders less gait) is the counterpart of cau compensatory gait the bedside examination of gait involves tious gait, caused by the defective that reduces the stance taking a careful history and a detailed perception of instability and typically phase in the affected physical examination. Falls are a serious seen in patients with postural instabil limb to minimize pain; it complication of gait disturbances, and ity who have a poor awareness of their is associated with pain detecting a possible risk of falls should own falling risk. Note mediolateral instability) and the feet characterized by a that subjects should be asked about not thrown out with varying step length. The de impulsively (eg, a very any compensatory strategies used by gree of instability is the major determi rapid rise from a seated 11 the patient to overcome part of the nant of gait changes, best detectable position: the ‘‘rocket disability, ranging from subtle (eg, by asking patients to perform the sign’’). Typically, adopting a slower gait speed when tandem gait task (Supplemental Digi these patients have balance is subjectively reduced) to tal Content 8-2, links. Other darkness or eye closure (eg, basal ganglia diseases); this can examples of gait changes induced by markedly worsens gait; be masked by greater cortical ‘‘volun lower limb weakness are drag-to gait (in in vestibular ataxic gait, tary’’ gait control, which typically de which the feet are dragged rather than eye closure can cause a teriorates under dual tasks (see the lifted because of a weak push-off, as seen consistent unilateral deviation of walking. Mus tends and the trunk lurches forward) proximal muscles of lower limbs; it is cular weakness is another condition (Supplemental Digital Content 8-3, characterized by that frequently impairs gait. Other abnormalities of the legs of lateral trunk Proximal weakness is typically seen in might also impair gait. Many condi movements with an myopathies, myasthenia gravis, and tions leading to limb hypertonia cause exaggerated elevation Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome a stiff gait, characterized by leg exten of the hip. In contrast, distal weak each step (when unilateral) or scissor foot drop (the foot ness is typically seen in neuropathies and ing of the legs with bilateral circum landing loudly on the leads to a steppage gait. Spasticity is floor) and the advancing occurs when the weakness of distal the most common cause of a stiff gait leg is lifted high so that muscles of the lower limbs causes a foot and may be unilateral (as in hemi the toes can clear the drop (the foot landing loudly on the paresis; Supplemental Digital Content 8 ground. Patients suspected of having freezing of gait often walk normally in the examination room because excitement associated with the doctor’s visit can suppress it. However, repeated gait initiations, walking in tight quarters, turning, or performing secondary tasks may provoke freezing of gait. Abnormalities to be noted during turning movements include the ‘‘pivoting’’ strategy, where the trunk rotates stiffly (en bloc) with the legs, shuffling of the feet with multiple small steps, or even overt freezing of gait. Furthermore, dual-tasking (the simplest test is to start a routine conversation while walking) has a good predictive value for falls in cognitively impaired older adults because these patients try to perform both tasks equally well, but gait or balance can be compromised (‘‘stop walking when talking’’). Other examples of secondary tasks include avoiding obstacles or carrying objects such as a tray while walking. Impor can also be episodic, as in paroxysmal 14 patients are instructed tantly, spasticity is typically accompa dyskinesias or tics involving the to hurry up. Other destabilizing h A useful sign that Other causes of leg stiffness are stiff factors are hyperekplexia and other supports the clinical person syndrome, neuromyotonia, types of myoclonusVfor example, as suspicion of dystonic and myotonia (the latter also charac seen in postanoxic encephalopathy gait is the improvement terized by a variable degree of proxi (Lance-Adams syndrome), in which that occurs in gait mal and distal weakness).

Diseases

- Convulsions benign familial neonatal

- Loiasis

- Respiratory chain deficiency malformations

- Osteogenesis imperfecta congenita microcephaly and cataracts

- Boylan Dew Greco syndrome

- Karandikar Maria Kamble syndrome

- Carnevale Krajewska Fischetto syndrome

- Cataract dental syndrome

- Hunter Mcdonald syndrome